Elizabeth Olum lives in the Gatina neighborhood on the outskirts of Nairobi and runs a wholesale grocery store. Since 2014, she’s participated in a local financial experiment meant to boost trade in one of the most economically depressed regions of Kenya’s capital.

The concept is simple: Since many people don’t have enough Kenyan shillings to pay for for everyday expenses, the nonprofit Grassroots Economics has worked with community leaders to introduce a system of hyper-localized currencies. These currencies can be used at businesses like, say, Olum’s grocery store, or to pay school fees, effectively acting as a form of basic income. “The community currency has been of great value to me, because I am part of a network, one family,” Olum told Bloomberg Businessweek in November of last year.

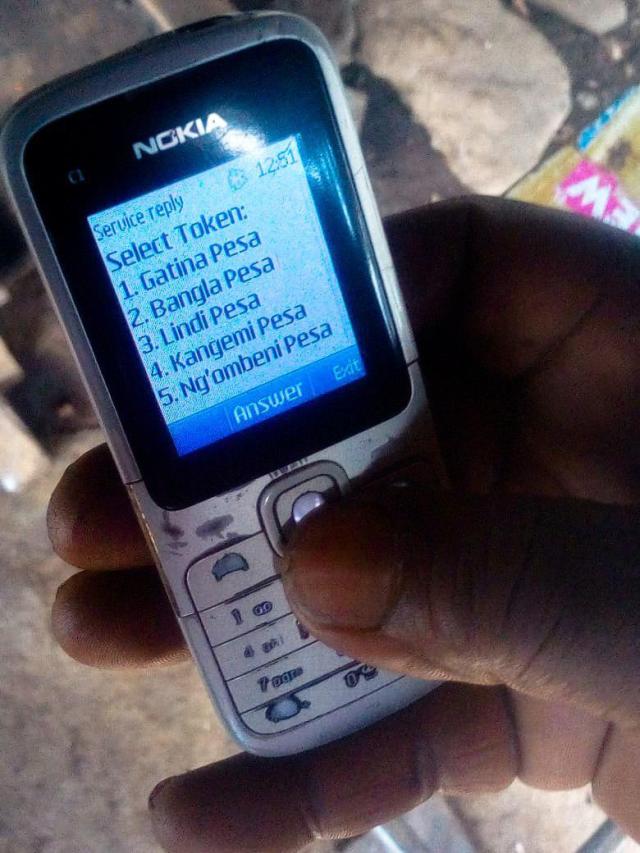

More recently, Grassroots Economics has partnered with decentralized liquidity network Bancor to put these hyper-localized systems on a blockchain. Rather than trading colorful physical papers, people in nine different Kenyan communities can now trade digital currency via smartphone crypto wallet or SMS texting. It’s called the Sarafu Network. (Sarafu means “currency” in Swahili.) For Olum, that means she can accept payment from not just her Gatina neighbors, but also from people who live in nearby villages. The Bancor protocol allows for greater interoperability of the tokens across different neighborhoods, meaning there’s greater liquidity and scalability than with other localized community currencies.

According to Bancor’s Q1 progress report, they’ve “identified specific regions in Kenya that are adopting the currencies at a rapid rate, with upwards of 70 percent penetration in certain target villages.” At present, approximately 2000 digital wallets are part of the Sarafu network.

The experiment is the brainchild of development economist Will Ruddick, who left his Stanford physics PhD program after becoming obsessed with economics and the ways in which additional currencies could complement official tender. “I think people in the West generally don’t realize how fragile the currency system is,” says Ruddick. “[In] Africa, the lack of a silly little piece of paper means that people aren’t eating, and people aren’t sending their kids to school, and people aren’t getting medical care. And yet, there’s this huge amount of goods and services that people can offer each other all the time.”

He started volunteering with local groups in 2010, building on relationships he had developed while working with the Peace Corps. “Part of the problem, and this is a narrative that you’ll hear in the community currency world, is that our economic system is just completely flawed—maybe flawed by design—but it promotes competition, and actively creates inequality, just mathematically,” he says.

Related: Too Many Cryptocurrencies? Not According to Bancor’s Galia Benartzi

Ruddick studied other examples of community currencies, like BerkShares in Massachusetts or LETS in Canada and elsewhere. Many of these projects emerged after periods of economic crises, instability, or stagnation. He says he was especially inspired by the work of economist Bernard Lietaer who was the co-creator of the European Currency Unit, the predecessor to the Euro. (Lietaer later served as president of the Bancor Protocol Foundation and its chief monetary officer, before his death in February of this year.)

“The first book I read about this was Bernard Lietaer’s [The Future of Money] and I was just in awe of it,” he says. “I just thought it was an amazing concept. [Community currencies] were a resilience mechanism, and the pattern was they all got outlawed when national government came back into power.”

Most Kenyans have a lot of familiarity with electronic money transfers already—the M-Pesa mobile payment option is ubiquitous, though one in five adults don’t have a bank account. But there’s a huge need for economic solutions. “I was super excited [when] I found out that Bancor was doing a grant program,” says Ruddick. “It was perfect because, really, this is what the founders of Bancor wanted to first place, was [to] create community currencies. Rarely in the tech industry do you get to design a product for a woman selling tomatoes.”

There’s some debate over how much of an impact these small-scale projects have on struggling economies, especially since some earlier community currencies eventually lost momentum. It’s a problem that Lietaer and Bancor’s founders had grappled with, said Nate Hindman, who is director of communications at Bancor.

“Often, we were finding that those types of economic ecosystems stagnated after a while. There’d be a big spike in usage, but because users, at the end of the day, couldn’t cash out their community currency or couldn’t use it on any items, or any goods or services outside of the community, we saw usage plateau or drop off,” he says. “The Bancor Protocol was this breakthrough in this kind of liquidity barrier, that has prevented community currencies from scaling and gaining widespread adoption.”

Ruddick has encountered obstacles along the way, however. Back in 2013, he and several others (who at the time were working on a precursor alternative currency, called the Bangla-Pesa) found themselves in legal trouble after an article was published in a Swahili newspaper suggesting that the project was part of a radical terrorist succession plot connected with al-Shabab.

Ruddick and several other local business owners were arrested and put in jail. Police were unsympathetic to his efforts to explain that the Bangla-Pesa was not intended to undermine the Kenyan shilling. Al Jazeera reported at the time that Ruddick and the rest of the Bangla-Pesa team spent more on lawyers, bail, and “fees for bureaucrats to re-find their files, which mysteriously kept getting lost” than the entire cost of the Bangla-Pesa program. “It was bad,” says Ruddick, who had a newborn daughter at the time of his arrest. “I essentially lost my wife and was a single dad after that. It definitely changed my whole life.”

Eventually, the charges were dropped and they received a letter from the Attorney General’s office saying that the project was, in fact, legal. To this day, Ruddick says the Central Bank doesn’t really acknowledge what they do. “We send them papers; they usually just don’t even stamp them. We always tell them what they’re doing. Everything’s above [board]—and nowadays, it’s all on the blockchain, too, so you can actually see all the trade that’s happening.”

"I think a really big question we're trying to answer is: What happens after the aid?”

More recently, things have settled down. Ruddick is raising his daughter and his parents have even retired to Kenya. He and the Bancor team say they’ve been fielding interest from many parties who want to try out similar pilot programs in their communities. They’re working with researchers to explore why and how programs like this can be effective and they’re eager to figure out ways to make it easy to transplant this sort of program. “I get requests constantly,” he says. “Partially because we’ve had a lot of media, but people are really desperate for an actual solution, and nothing in the aid industry is working—for 30 years.”

Hindman says that different aid methods such as cash transfer (which is often seen as more effective and transparent than other forms of humanitarian aid) can still fall short. “I think a really big question we’re trying to answer is: What happens after the aid?” he says. “Groups will dump money on a community and that money will eventually just get dissipated and leave the community. How do we put money onto a community and have it create sustainable loops of commerce?”

So far they’ve seen a lot of use from Kenyan women in particular, with 69 percent of network transactions being carried out by women. Certain villages have even higher rates: Mkanyeni and Kibera boast 95 percent and 87 percent female enrollment, respectively.

“If you go in impoverished areas, you’ll find that most of the businesses on the road, there are women in those stalls,” says Ruddick. “What we’re doing right now is filling this gap that’s been left by male-dominated culture, that’s been left by ultra-capitalism. [It’s] pushed value out of the people and into the pockets of the rich. And at the same time, that gap represents a huge amount of value.”

Photos courtesy Bancor.