When Lyn Ulbricht is home, a 20-minute drive from the maximum-security penitentiary in Florence, Colo., she’s frequently up at five in the morning. After fixing herself a cup of tea and doing some devotional reading, she turns to meditation and prayer. She often visualizes her son Ross—who until a recent transfer was locked up in that nearby penitentiary—as a free man. Sometimes she pictures him emerging from prison to be greeted by a celebratory group of family and friends. Other times she imagines feeding him a good, home-cooked meal. Or she envisions spending time with him on the beach, like they used to do on family vacations in Costa Rica, before Ross was arrested and Lyn’s life changed in ways she could never have imagined.

But on this early November day, Lyn Ulbricht is in Las Vegas, sitting at a booth at World Crypto Con at the Aria Resort and Casino on the Strip. On the table in front of her are piles of FreeRoss.org stickers and fliers; a clear plastic box for cash donations; a mailing list sign-up sheet; and a pad of purple, butterfly-emblazoned stationery available for anyone looking to write Ross, now 34, a note in prison. Behind her are two banners, one bearing a charcoal-style portrait of Ross and the message “Help free Ross Ulbricht! Our Goal: 500,000 Signatures.”

To Lyn’s left hangs Silk Road, a painting of a caravan of camels by Finnish artist Vesa Kivinen, which is being auctioned off to help support the Free Ross campaign. The work shares its name with the infamous dark web bazaar Ross founded in early 2011, where all manner of drugs and other illicit goods were available. After a lengthy, multiagency investigation, the FBI arrested Ross in 2013, accusing him of running the eBay-like site under the alias the Dread Pirate Roberts. In 2015, he was convicted of seven counts, including distributing narcotics on the internet and engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, and was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Lyn stands out in a sea of young, male conventioneers in altcoin T-shirts. A petite, blonde woman in her sixties, she is dressed in black slacks and an unbuttoned white collared shirt over a long-sleeve slate-blue tee. She’s wearing a black fanny pack, just big enough to carry her iPhone. Though she was a tech neophyte not terribly long ago—she only got her first smartphone, a hand-me-down, two weeks before Ross’s arrest—she now feels, if not at home, at least at ease among all the blockchain and cryptocurrency startups that share the floor with her.

While she’s here, Lyn will work the booth, give a talk, and participate in some podcasts and documentaries—all fairly typical activities for her. But she makes sure to leave some flexibility in her schedule to go with what she describes as a “very strong flow.” She likens it to surfing, once a pastime of Ross’s. Sometimes things happen, or people come her way, that Lyn, a Christian, attributes to a higher power. The flow, or God, can take her surprising places. By the end of her time in Vegas, she will have sat down for a joint interview with a man Ross is alleged to have ordered killed, and snagged a MAGA rally photo-op with Donald Trump Jr.

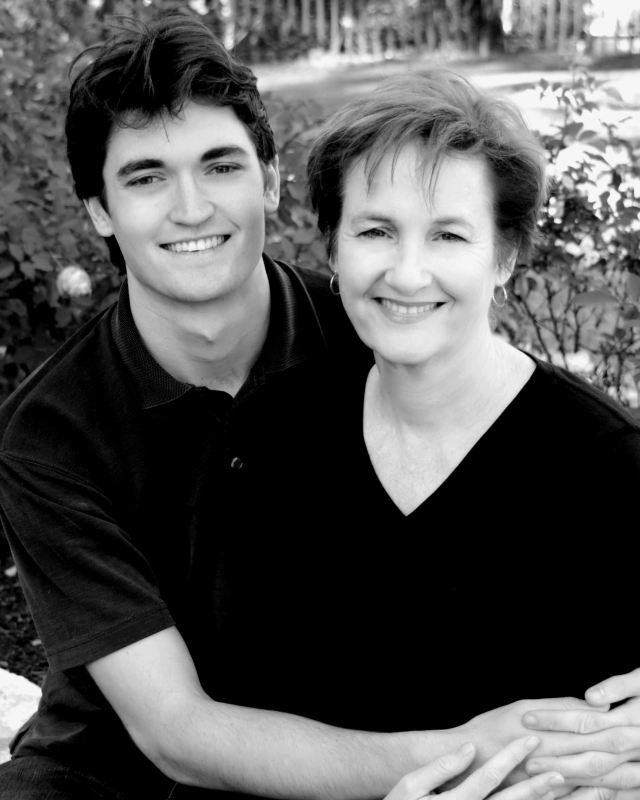

“My prayer is that I go free and can have kids of my own and show them at least a fraction of the love [my mom] and my dad have shown me,” Ross writes.

This image and main photo courtesy Lyn Ulbricht

At the moment, Lyn is speaking with a grey-bearded man named T.J. Rohleder, whom I later learn is an entrepreneur and prolific author of excitedly titled books (How to Make Millions Sitting on Your Ass!). Rohleder, who calls himself the Blue Jeans Millionaire, is wearing wire-framed glasses, an orange Carhartt pocket tee, and yes, blue jeans. He’s an advisor for a cryptocurrency investment group. “I read about you in Rolling Stone magazine,” he tells Lyn.

“Oh God, I hated that article!” she replies.

“Well, it’s the only way I know about this.”

“Well, that’s too bad because it was very distorted. And that guy who wrote it was so horrible. Don’t believe that story!”

Lyn and her husband Kirk regret participating in that 2014 feature, which is the basis for an upcoming movie. She begins to explain how the piece was sensationalized, how it focused on unproven allegations of murder-for-hire. (Look no further than the secondary headline: “It was the eBay of vice, an online hub of guns, drugs and crime. But its alleged founder soon learned that you can’t rule the underworld without spilling some blood.”)

The Blue Jeans Millionaire interrupts her. “I actually read that story through the eyes of an entrepreneur,” Rohleder says, adding that he believes in freedom and independence and the right to not have the government tell us how to live.

“Well, you saw past the sensationalism,” Lyn says. For five years, she has fought the mainstream media narrative—which she says made “Ross into this monster, this kind of Breaking Bad character”—and explained time and again why her son deserves his freedom. She has suffered her share of brutal losses, but this conversation is a small win: Rohleder says he’ll sign the online petition calling for clemency for Ross.

Lyn’s plan is to, one way or another, present President Trump with the petition once it reaches half a million signatures. (As of this writing, it has more than 128,000.) Her son has all but run out of legal options; the president is the only person who can grant him clemency.

“Mother’s love, man, it’s a powerful thing,” Rohleder says. “It’s the most powerful thing.”

Lyn smiles appreciatively. “Don’t mess with the mama,” she says.

Ross was arrested in San Francisco on Oct. 1, 2013, something Lyn didn’t learn until the next day, when a Reuters reporter called her and Kirk at their home in Austin seeking comment. The allegation that Ross was the mastermind behind Silk Road came as a complete shock to the couple, the operators of an eco-resort in Costa Rica. “He is a really stellar, good person and very idealistic,” Lyn told Reuters. “I know he never meant to hurt anyone.” It’s a position she hasn’t wavered from since.

Things escalated quickly from there. “We turn on the TV, and I’m hearing George Stephanopoulos go, ‘Oh yeah, this guy did this,’” Lyn says. “And I’m like, ‘What are you talking about?’” Emails poured in, the phone rang relentlessly, journalists kept knocking on their front door. “It was like a siege,” she says.

It took a few days before Ross was finally able to reach Lyn on the phone. She recalls him saying, “Sorry to be a bother, Mom.”

Lyn was taken aback at how the kind, gentle kid she’d raised was being portrayed in the press. And thus, just a few weeks after her son’s arrest, she launched FreeRoss.org. “I believe Ross Ulbricht is innocent of all the charges brought against him,” she later wrote on the site’s blog. “I often hear, ‘Of course you do. You’re his mother.’ True, but my opinion is not simply based on emotion. The charges just don’t add up. And they are antithetical to Ross’ character and how he lived.”

“I went in there thinking, ‘Okay, this is going to be challenging, but we’re in America. We have a justice system that I can rely on to be fair.' And I was absolutely shocked by the trial."

In January 2014, Lyn and Kirk relocated from Texas to Connecticut to be closer to Ross, then being held at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. A year later, they attended Ross’s trial in Manhattan federal district court. Lyn says the trial’s 11 days, spread out over more than three weeks, were among the worst of her life. “I went in there thinking, ‘Okay, this is going to be challenging, but we’re in America. We have a justice system that I can rely on to be fair,’” she says. “And I was absolutely shocked by the trial. The defense was shut down time and again.”

Prosecutors portrayed Ross as a digital kingpin who had run Silk Road as Dread Pirate Roberts, or DPR, for the entirety of the site’s existence. According to the government, there were more than 1.5 million transactions on the site—all using bitcoin—and nearly $183 million in illegal drug sales. Prosecutors said that Ross had taken in millions of dollars in commissions from deals made on Silk Road and accused him of ordering the murders of half a dozen people he perceived as threats to the site. (The prosecution said it did not believe any of those killings had been carried out.)

The defense admitted that Ross, who did not take the stand, had created Silk Road, but argued that it was merely an “economic experiment” and that he had handed the reins off to other individuals after only a few months. During closing arguments, lead defense attorney Joshua L. Dratel told jurors that the incriminating information authorities seized from Ross’s laptop could have been created by others and called Ross the “fall guy” for Silk Road’s actual operators.

Prosecutors countered that the evidence, including a journal and chat logs taken from Ross’s laptop, showed that he was indeed DPR. “There’s no dispute when the defendant was arrested, he was logged in as Dread Pirate Roberts,” prosecutor Serrin Turner told the jury. “There were no little elves that put all of that evidence on the defendant’s computer.”

It took a jury about three and a half hours to convict Ross of all seven counts against him. When the verdicts were read in the courtroom, Lyn shook her head slowly. “It was devastating,” she says.

The sentencing was even harder on her. In late May 2014, Judge Katherine B. Forrest handed down the most severe sentence possible, more than even prosecutors had sought: two life terms plus 40 years, with no chance for parole. “The stated purpose [of Silk Road] was to be beyond the law,” Forrest told Ross. “In the world you created over time, democracy didn’t exist. You were captain of the ship, the Dread Pirate Roberts. You made your own laws.” During the sentencing, Forrest cited the murder-for-hire allegations, although Ross had not been tried for them.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

Lyn has many words for the sentence: “egregious,” “barbaric,” “draconian,” “outrageous,” “unbelievable.” “I think about it now, and I want to start to cry,” she says. She stresses that Ross was a first-time offender, convicted of all nonviolent crimes, and says that the judge was seeking to make an example of him. “If District Court Judge Katherine Forrest has her way,” Lyn wrote on her son’s most recent birthday, “Ross will spend all his future birthdays [in prison] too, until he is carried out as a corpse.”

Last summer, upon news of Forrest’s retirement, Ross publicly wished her “happiness and peace.” Lyn is by no means at that stage yet. “I’m asking God to help me forgive this woman,” she says. “I think she was really horrible.” Yet Lyn says she hasn’t become bitter. “I’m angry,” she says. “There’s a difference. I’m angry at the system.” She’s disciplined herself not to dwell on what she sees as a miscarriage of justice. “It’s only going to hurt me and enervate me and stop me from being effective,” she says. “So I try to focus on what’s positive: What can I do? What can I get done?”

Lyn LaCava grew up in a good neighborhood in Bronxville, N.Y., just north of Manhattan. Her mother was a homemaker who, Lyn says, “felt the pain of other people”; as a college student in North Carolina in the mid-’40s, her mom rode in the back of the bus with the black passengers in a show of solidarity. Lyn’s father was a Madison Avenue advertising executive and the son of entertainers: Beryl Morse, a Broadway actress and distant cousin of the inventor of Morse Code, and Gregory La Cava, the Oscar-nominated director of 1930s films My Man Godfrey and Stage Door.

The oldest of five sisters, Lyn says she had a “big mouth” from an early age. This wasn’t unusual in her family; Lyn and her next oldest sibling, now Kim Reisinger, both use same word—“verbal”—to describe all the women of the household. “Lyn read, and she was articulate, and she would stand up and challenge people—kind of like she does now,” Reisinger recalls.

After graduating from Skidmore College, Lyn attended journalism school at the University of Missouri, where she honed the writing and editing skills that she uses so often today. From there, she relocated to San Francisco, working for a time at a small public relations agency—more training for Free Ross. In the late ’70s, Lyn moved to Los Angeles with plans to write a book about her famous grandfather. She didn’t get far with that project, but she did meet a laid-back Texan named Kirk Ulbricht, in town visiting his son from his first marriage.

Lyn, Cally, Ross, and Kirk Ulbricht

Photo courtesy Lyn Ulbricht

She and Kirk got married and moved to Austin in 1978. The next year, the couple had their first child, a daughter named Cally, who now lives in Sydney and works in marketing. Ross was born on March 27, 1984. He was “a healthy, happy, unflappable Buddha of a kid,” Kirk has said. Ross would follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming an Eagle Scout. (It’s a detail both Lyn and the media have emphasized, to different ends: She to illustrate Ross’s good character, the press to better establish his story arc.)

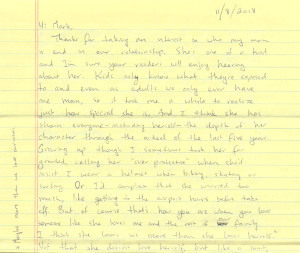

Lyn describes herself as a “pretty big pushover” when it came to parenting. Ross saw it differently. “[I’d call] her ‘overprotective’ when she’d insist I wear a helmet when biking, skating, or surfing,” Ross says in a handwritten letter to BREAKERMAG. Lyn encouraged him to play outside or develop his talent for drawing. “I hated it when she would say, ‘Break the spell,’ and click off the TV,” he writes. Lyn would respond, “You’ll thank me when you’re older.”

To outsiders, Lyn was the mother they wish they had, according to Cally. “All my friends would stay over at my house, and everyone was like, ‘Oh, your mom is really cool.’” It’s a dynamic that continues to this day. At the conference, Lyn is orbited by a handful of younger female friends, all of whom she’s met in recent years: crypto attorney Sasha Hodder, singer-songwriter Tatiana Moroz, and film producer Mimi Riley. “I live far away from my own mother,” says Hodder, who hosted Lyn at her home in Florida last year. “Having Lyn there was like having my own mom around.”

Now that he’s older, Ross says he does indeed thank Lyn for clicking off the TV. Likewise, he appreciates that she keeps on him about flossing and taking his vitamins in prison. Though Ross admits he sometimes took his mom for granted in his youth—what kid doesn’t?—today he considers himself and Lyn “more like friends.” Ross sees, through adult eyes, the depth of her affection for him and their family. “I think she loves us more than she loves herself,” he writes, adding a footnote in the margin: “Maybe more than we love ourselves.”

Lyn first began getting invited to cryptocurrency conferences last year. It’s a good fit: The cryptosphere is, to put it in political terms, the Ulbrichts’s base. Bitcoin.com CEO Roger Ver, ShapeShift CEO Erik Voorhees, Litecoin creator Charlie Lee, and antivirus pioneer and crypto evangelist John McAfee are all supporters. At World Crypto Con, Civic CEO Vinny Lingham made an onstage bet with Standpoint Research founder Ronnie Moas that bitcoin’s price won’t hit $28,000 by the end of 2019. The amount of the wager: a $20,000 donation to the Free Ross campaign.

The crypto community owes Ross a great deal, his backers argue: Silk Road was the proof of concept that the then-fledgling bitcoin needed, dramatically speeding up the adoption of digital currency. Plus, some in the space empathize with Ross because they’re intensely distrustful of the government that brought him down. “I think the U.S. government is one of the biggest threats to world peace ever,” says Ver, who has corresponded with Ross. “And so, of course, they’re busy throwing good people like Ross in jail.”

Blockchain journalist David Gerard, however, argues that such distrust blinds people to what he sees as Ross’s certain guilt. “They had this big hope, and the hope didn’t work out, and they’re sure that it’s all a scam—that the government and the courts are all in it together to crush the vital spirit of rebuilding the world in the anarchist ideal,” Gerard says. He adds that it’s “worth pushing back on” some issues with the case (“Like, was the evidence tainted? Was Ross really just railroaded into buying murders?”), but thinks that Ross’s supporters tend to dismiss or discount the facts. “There’s a lot of wishful thinking in the Free Ross movement, and the wishful thinking does the movement no credit.”

No matter what you believe Ross did, it’s hard to hold anything against his mother. “I especially don’t want to be harsh on Lyn Ulbricht,” Gerard says. “Of course she’s going to pursue this.” Lyn says she’s fielded some challenging questions at talks, but rarely gets attacked personally. Says Ver, “There are maybe two people in the crypto community that pretty much everybody likes. One is that guy Dorian Nakamoto”—the hapless older gentleman whom Newsweek famously misidentified as bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto—“and the other is Lyn Ulbricht.”

Lyn and some new friends at World Crypto Con

Photo by Mark Yarm

Among some of the Free Ross crowd, there’s also a sense of “there but for the grace of God go I.” (As Ver is quick to volunteer, he himself has served time in prison.) At one point, a lean, middle-aged computer-services business owner named Alan stops by Lyn’s booth to share his own story. As a young man, he tells Lyn, he engaged in “exploratory” hacking. “I did that for many, many years, and I got into hundreds and hundreds of systems I shouldn’t have been into,” Alan says, crouching tableside. “And the line is so fine that, if the circumstances would have been just ever so slightly different, you know…” He trails off, his lower lip quivering.

Lyn hears this kind of thing all the time. But she realizes the limits of the case’s emotional appeal. “My talks are much more ‘This is the precedent, this is why it matters,’ because I figure there’s just so much of ‘My poor son, please feel bad for me’ people can take,” she says. “Also, they don’t know Ross, so why should people care after a while? But if it’s something that affects you, or affects your future, because of the precedents that are being set, that’s different. When it’s about your privacy or due process, that’s different.”

Director Alex Winter, who interviewed Ross’s parents for his 2015 documentary Deep Web, says he was immediately struck “by just how quickly and how astutely” Lyn had grasped the complex issues at play in the case. “She became an expert in surveillance, privacy, First and Fourth Amendment,” Winter says. Lyn has adapted to our digital era better than many, Ver says: “The fact that she figured out how to set up PGP encryption for email really shows just how smart a lady she is. I wish my mother would learn how to use PGP email.”

Lyn also has become a vocal critic of the drug war, which has been filling the prisons with nonviolent offenders for decades. “I’ve met some of the inmates in the visiting area,” she says. “I’ve talked to their families. Gotten to know their children. I see the damage it’s doing to those children and the likelihood that they will end up in prison too—and that it’s a big money-making, power-grabbing machine.”

As Lyn tells me this in Vegas, Ross is being held in the SHU, aka “the hole,” at the prison in Florence for protective reasons. She says he refused to participate in the assault of another inmate, which made him a target. (“It’s never ok to initiate violence,” Ross relays to his followers via @RealRossU, a Twitter account run by a friend of the family who communicates with him by phone and mail.) He will finally get out of the SHU in late December, after a total of 105 days. A few weeks later, he is transferred to what Lyn describes as a much safer penitentiary in Tucson, Ariz. She likely will move to Arizona in the spring to be closer to him.

When Ross is released from prison altogether—it’s always “when,” not “if”—Lyn says she will take a nice long vacation, then resume speaking out on criminal justice and prison reform. “Because you can’t forget it once you’ve seen it,” she says.

On the second full day of the conference, I meet Curtis Green, a heavyset 53-year-old Mormon grandfather and former semi-pro poker player from Utah. Green thinks highly of Lyn (“She’s a fantastic lady”) and signed the Free Ross petition as soon as he found out about it. He says he’d sign it twice if he could. “Whether you think Ross is guilty or not,” he says, “the one thing that I think everybody agrees with is the sentence that he received was overboard.”

Green’s attorneys, on the other hand, can’t believe he’s taking Ross’s side. “They’re like, ‘He tried to have you killed. Why are you doing that?’”

Green was a Silk Road moderator–turned–paid administrator who went by the screennames Chronicpain and Flush. His story is a complicated one—he’s written a book about it—but the gist of it is this: In January 2013, the authorities battered down Green’s door after he opened a package of cocaine delivered to his home. DPR learned of the arrest, and fearing that Green would cooperate with law enforcement, allegedly took out a hit on him through a Silk Road confidante named Nob. Turns out that Nob was a DEA agent named Carl Force, and that Green was, in fact, cooperating with the feds. Nob sent DPR a photo of Green—face smeared with chicken soup to make it appear he’d been asphyxiated—to prove that the murder had been carried out.

Ross was charged with plotting to kill Green, but the case was ultimately dismissed last summer. He was never charged in the other alleged murder-for-hire plots, which apparently stemmed from an elaborate blackmail scam targeting DPR. Lyn argues that prosecutors prejudiced the jury by bringing up the unproven murder-for-hire allegations at trial. “It should not have been permitted,” Lyn tells me. “It was almost like, ‘Well, he did it, just trust us.’”

Green has met Lyn in person once before, in 2017 at a New York diner, where they discussed particulars of the case over breakfast and found they liked one another. Today, in a large convention conference room, they’re meeting again, to make a joint appearance on The Crypto Show podcast. The unlikely pair, both dressed in black, sit across a table from silver-haired host Danny Sessom, who proves extremely well-versed in the Silk Road saga.

The Crypto Show host Danny Sessom (left) interviews Curtis Green and Lyn Ulbricht

Photo by Mark Yarm

A good deal of the podcast discussion revolves around Carl Force and Shaun Bridges, a Secret Service agent on Force’s team. In 2015, Force was sentenced to six and a half years in prison for stealing bitcoin during the Silk Road investigation and attempting to extort DPR. Later that year, Bridges got nearly six years for stealing more than $800,000 worth of bitcoin from Silk Road during the probe. In 2017, Bridges was sentenced to two more years for stealing additional Silk Road funds.

Lyn expresses dismay that none of the allegations against the corrupt agents—whom, she points out, “had the ability to change all kinds of things on the site”—were allowed to come up at Ross’s trial. Green and Lyn talk about how there were seemingly multiple DPRs; Green says he himself acted as DPR on occasion, and Lyn points out that someone apparently logged in as DPR after Ross was arrested. They agree on most everything, though Green hedges when Sessom asks whether there’s any part of him that thinks Ross ordered the hit against him.

“Some days I would say, ‘Oh, yes. It has to be,’” Green says. “Then other days I would wake up and say, ‘No, it couldn’t, because of this.’ And I was just killing myself trying to figure things out. And I decided, you know what, I’m not gonna ever know for sure. You know, we will all never know for sure.”

Later, Lyn asks Green if he’d be worried to hear Ross was getting out of prison.

“Oh, heck—heavens, no,” he says.

“Or would you be willing to have him over to dinner and hang out?”

“Yeah, I—”

“OK. Thank you!” Lyn smiles, satisfied. It strikes me later that she’d make an effective courtroom attorney.

“I wanna go talk to him,” Green adds.

“Wait a minute,” Sessom says. “Would you be worried when Force and—”

Green cuts him off before he can say Bridges’s name. “I am worried as hell,” he says. Lyn throws back her head, letting out a hearty laugh and clapping her hands.

“I’m counting the days when they get out,” Green adds. “That’s when I’m gonna seriously think about my safety. Not so much Force, but Bridges. He scares the bejesus out of me.”

Lyn’s point has been made. It’s another small win.

Those who know Lyn often use the word “tireless” to describe her. Which is true in spirit, but not entirely accurate. All the traveling, in particular, is exhausting. The stress can be overwhelming. In fact, it nearly killed her once.

Lyn started feeling ill in September 2015, during a speaking tour of Eastern Europe. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘Dear God, she’s playing the Ross Show on loop all day, every day,” says Tatiana Moroz, the singer-songwriter, who was traveling with Lyn at the time. “It was just nonstop, from morning till night, fear and pain and misery.” By the time Lyn reached Warsaw, she was incapacitated. “What’s happening is I’m having heart failure and I don’t know it,” she says. Lyn returned home, to Connecticut, where she ended up in the ICU for a week before being released.

The next day, back at home, with her sister Ann Becket and Ann’s husband Peter visiting, Lyn collapsed on the couch. Her heart stopped completely, and she began turning blue. With coaching from a 911 dispatcher, her brother-in-law, an ex-Marine, was able to administer CPR, keeping her alive. Lyn was helicoptered to Hartford, where she was hospitalized for about three weeks. Doctors determined that she had suffered takotsubo cardiomyopathy, heart failure brought on by emotional stress. Its more common name: broken heart syndrome.

Lyn says that she, to the amazement of her doctors, experienced no lasting damage. “I guess I’m meant to do more stuff,” she says. In the wake of her illness, she quit working for the family’s Costa Rican resort to focus exclusively on Ross’s case. (Kirk now runs the business with assistance from a property manager.) Ross believes his mom has slowed down—“in part because she recognizes she can’t help me if she’s dead!”—but Lyn says that she probably works just as hard as she did before. Back in Colorado, she spends long hours in front of the computer, emailing with lawyers, volunteers, the press, you name it. (She’s involved in running the Free Ross social media accounts, but a good deal of that work is now done by Cally and some volunteers.)

Ross describes his mother’s grief as so deep that she feels like she has nothing left to lose. “She feels the loss and separation every day,” he writes. “So she does what she can every day because she can’t go on [otherwise] while I’m in here. She says, ‘What am I going to do, go to the beach while you’re still in there? I’ve got emails to follow up on.’”

In May 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld Ross’s conviction and sentence. Last June, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider Ross’s case. Today, what’s known as a habeas petition is his only legal recourse. His lawyers are still pursuing that avenue—an extreme longshot—but Lyn has increasingly focused her efforts on shifting the political tides. “It’s people and paperwork,” she says. “The president is a human being, I’m a human being, Ross is a human being, and the paperwork is a commutation—a piece of paper with a signature on it. It’s not like I’m trying to physically move a mountain. You know, it’s possible.”

She’s made some progress on the political front. One victory came at last summer’s Libertarian National Convention in New Orleans, where conventioneers unanimously passed a resolution calling upon Trump “to issue a full pardon” for Ross. On the face of it, Libertarianism, with its emphasis on free markets, seems an easy fit with the Silk Road case. (Also, Ross himself is a libertarian.) But the resolution was still hard-won, says party member Jeffrey Tucker, the editorial director of the American Institute for Economic Research.

“Once a murder-for-hire charge made the New York Times, libertarians dropped him like a hot potato,” says Tucker, a friend of Lyn’s. It was left to Ross’s mother to “flip the script,” he adds: “With enough speeches, enough traveling, enough interviews, and enough podcasts, she was able to convince people that are interested in human rights that he was a worthy cause of support. That was entirely her doing.”

What matters most to Lyn now is not whether you’re a Libertarian or a Democrat or a Republican, but whether you want to Free Ross. Which means she’ll gladly accept support from some controversial political figures, like InfoWars host Alex Jones, whose show she’s been a guest on. “I really can’t be picky,” Lyn says. “But let me get clear: I’m not saying I would align myself with someone that I thought was evil or extreme.”

Shortly after I leave World Crypto Con, Lyn strengthens her alliance with another divisive figure: Mike Cernovich, the alt-right social-media personality and Pizzagate conspiracy theorist. A crypto enthusiast and vocal Ross advocate, Cernovich connected with Lyn at the convention and suggested she make a video appeal to President Trump. Cernovich shot Lyn on his phone and tweeted the 26-second clip out to his nearly 450,000 followers.

That evening, Cernovich took Lyn to a rally for Republican congressional candidate Danny Tarkanian, at Stoney’s Rockin’ Country, a honky-tonk bar at the south end of the Strip. The draw: an appearance by Donald Trump Jr. After his speech, Trump Jr. was swarmed by the MAGA crowd—“It was pretty much a madhouse,” Lyn says—but she managed to grab a quick photo with him. She had no chance to plead Ross’s case, but she has that picture, which she tweeted a few days later, tagging the president and members of his family.

Who knows what could happen because of that one tweet? “One of the benefits of the chaotic nature of the Trump presidency is that you feel like as an individual actor maybe you can get seen,” Cernovich says. Both he and Lyn cite the fact that last summer Trump commuted the sentence of Alice Marie Johnson, a 63-year-old woman serving life in prison for a nonviolent drug conviction, after Kim Kardashian met with him in the White House and lobbied on Johnson’s behalf. (Ross has written to Kardashian about his case, hoping for a similar assist, but has heard nothing back.)

“Rather than being like, ‘What’s Kim Kardashian doing at the White House?’ I think the better approach is Lyn’s, which is, ‘How do I get in the White House?’” Cernovich says. “‘How do I just get five minutes of his time and maybe pull at his heartstrings?’ She gets it.”

Back at Lyn’s convention table, she and I had discussed just how unpredictable Trump can be. “I like that,” she said, smiling and pointing an index finger skyward. “The Justice Department’s extremely predictable, so at least with someone who’s unpredictable there’s hope.”

Ross holds out hope, too. He hopes, in part, to someday emulate his mother. “My prayer is that I go free and can have kids of my own and show them at least a fraction of the love she and my dad have shown me,” he writes. “They will be lucky kids if I can live up to that.”

Lyn would love grandchildren from Ross, though she acknowledges that she may not live long enough to see that happen. Again, she refuses to dwell on such dark thoughts.

“You know, things can change,” Lyn says at the end of our last phone conversation together. “Laws can change. Decisions can change.”

She returns to her mantra: “It’s just people and paperwork.”