“Why do I need bitcoin?”

I get that question a lot from my friends.

The truth is that they don’t need bitcoin. Not really. Their credit cards work fine. ATMs reliably spit out cash. Tomorrow, the U.S. dollar will have the same purchasing power that it does today. On a philosophical level, sure, there are plenty of arguments for a decentralized currency, but in terms of what’s in it for me, at the moment, crypto is about as useful as lugging around a second umbrella.

This is not the case in much of Latin America.

Consider the case of Eugenia Alcalá, a psychologist. She’s a Venezuelan who lives in Caracas. A few months ago, her husband needed an MRI. The hospital scheduled the MRI for a Friday, and said it would cost 350 Bolivars. A scheduling mishap bumped the MRI to Monday… and by then the cost had doubled.

“I had a friend, a psychologist, who died of pulmonary infection because there were no antibiotics,” says Alcalá. “Not because he couldn’t afford it. But because there was no medicine available in the city.”

That’s just a typical day-in-the-life of Caracas, says Alcalá. Credit card limits are unable to keep pace with hyperinflation—imagine that your MasterCard has a limit of $5,000, but a loaf of bread costs $1,000 today and $2,000 next week. Alcalá knows a married couple—an engineer and a doctor—who skip dinners so their children can eat. Cash is scarce, so it’s hard to buy things like bus tickets. “Construction workers camp on the street near the construction sites, because they can’t get a ticket home,” says Alcalá. “It’s surreal.” These problems cascade into others. “I had a friend, a psychologist, who died of pulmonary infection because there were no antibiotics,” she says. “Not because he couldn’t afford it. But because there was no medicine available in the city.”

Her voice cracking with emotion, Alcalá unspools story after story: the friend who needed three credit cards to restock a first aid kit; the child who needed heart surgery, but whose parents couldn’t find a single hospital to perform the operation (all of the necessary equipment had been stolen); the guy who brought his family and friends to the store so he could buy a refrigerator, pooling together all of their credit cards. “I have five banks,” she says. “And I have a debit and credit card for each of those banks.” Thanks to these 10 cards, she’s able to do her weekly grocery shopping.

Alcalá eventually found a solution, or at least a partial solution: crypto.

Paving New Highways

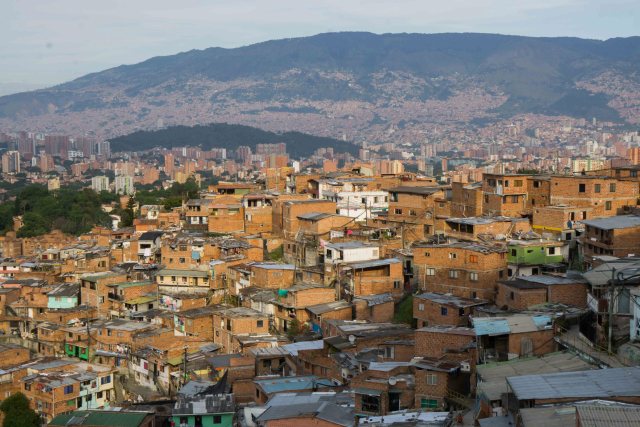

Let me back up. I learned about Alcalá when I traveled to Medellin, Colombia—Venezuela’s western neighbor that (for now) is spared the carnage of hyperinflation. Much of Medellin is safe and gorgeous and packed with culture, yet thanks to the lingering stigma of its well-documented cocaine wars, you can live a high quality of life on something of a bargain; the city has quietly transformed into a haven for remote workers.

As for crypto? Whenever I visit a new country, one of the first things I do is troll MeetUp.com for upcoming blockchain events. (Reason #347 I’m single.) In Medellin I see something odd: The next two dozen meet-ups are all cluttered with invitations from Dash. They offer lunches and freebies: If you install a Dash wallet, you’ll get a free slice of pizza!

This is weird. I’ve been to 20 countries in the past year, and I’ve never seen that kind of hyper-aggressive promotion. The promotions look like a throwback, almost schlocky—the cheapo coupons that you’d see in the Yellow Pages, back when the world had Yellow Pages. Why the Dash-a-thon? Why Colombia?

I do a little digging, attend a Medellin blockchain conference, and soon meet with George Donnelly, who heads up Dash Colombia. We meet at a coworking space called Selina that has a tattoo shop, DJ booth, meditation room, tastefully grafted walls, and a massive outdoor restaurant with a retractable roof. The place is colorful, bold, loud, funky. I like it.

“Latin America is unique,” says Donnelly, who’s originally from Philadelphia, and moved here in 2001. He says that parts of Latin America have a rare combination of three variables: strong electrical and internet infrastructure, weak governments, and a large pool of people. “That’s why Dash is building here. This is the place where it’s going to happen.”

Donnelly cites the work of Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto Polar, who argued that there are billions of people stuck in an “informal economy” that lacks the banks, credit, and other financial goodies that the rest of us take for granted. (These are the “unbanked,” often referenced by the bitcoin champions.) De Soto wrote that there are “two parallel economies, legal and extra legal. An elite minority enjoys the economic benefits of the law and globalization, while the majority of entrepreneurs are stuck in poverty, where their assets…languish as dead capital in the shadows of the law.”

Colombia fits this profile. Sixty-four percent of the country’s employment is informal, according to WorldAtlas, making it the seventh most informal economy on the planet. The list’s top 10, in fact, is dominated by Latin American countries—Guatemala, Honduras, Peru, El Salvador, Paraguay, Mexico, Dominican Republic.

“Fintech is a huge problem here,” says Jose Gaviria, a local blockchain consultant. In a lunch break at the conference, Gaviria ticks off the problems in Colombia. “People don’t have access to banks. These people don’t have credit identities. Blockchain can help solve this.” In something of a paradox, Colombia’s lack of infrastructure could make it easier to implement blockchain solutions. (This is also known as the leapfrogging concept, the idea that developing countries—without the scaffolding of legacy banks—can harness blockchain to do things better.) At the lunch, someone from the Blockchain Centre gives me an analogy: “What would be harder? Going to the U.S. and changing your entire highway system, or paving new highways in an empty country?”

Guaranteed Money

When I speak to a dozen or so locals about cryptocurrencies in Medellin, almost every single one brings up the same word: scams. They hit Colombia hard. “There’s a lack of opportunity in Colombia to make money,” says Felipe Cano, director of Blockchain Centre in Colombia. “And when people see an easy way to make money, they take it, even if they don’t really understand what it is.”

There have been at least three big scams in Colombia: GladiaCoin, OneCoin, and MeCoin. They generally “guaranteed” people insane returns in a quick turnaround: Give us $1,000 now, and we guarantee you $2,000 in a month. “These attracted people from all over Latin America,” says Dwayne Golden, the CEO of CoinLogiq, which makes bitcoin ATMs in Colombia. They used a pyramid scheme structure where, once you’re onboard, you give this “investment” your own personal imprimatur, which lassos your friends and family.

As is often the case with pyramid schemes, often these scams would work… at first. You pump in 3.2 million Colombian pesos (the equivalent of $1,000 U.S. dollars) and then, presto, you would indeed see 6.4 million pesos. Magic! So then you put more chips on the table. Maybe you take out a loan, or liquidate your college savings account. “People who have a lot less to lose, and everything to gain, are going to participate in these at a much higher frequency,” says Golden. “Scams are always going to be more popular in Latin America.”

The scams hurt crypto’s reputation from the jump, but Golden says that, ironically, they helped raise the overall awareness of cryptocurrencies. “Now we need to create a positive adoption based on something substantive, not hocus pocus,” he says. While the Colombian government is wary of scams, it’s more receptive to the underlying technology. (“Blockchain, not bitcoin,” is a trend seen around the globe.) “They want blockchain, but without the cryptocurrencies,” says Rafael Torres, the Colombian ambassador for NEM, another cryptocurrency.

I visit the offices of the Blockchain Centre of Colombia, where the director, Felipe Canon, has set up a glass box stuffed with Venezuelan Bolivars. The box is about the size of a toaster oven. It is crammed with bills. “All of that is worth $3,” says Canon. He keeps it there as a reminder for why crypto matters. Canon says that his center is working with the Colombian government to create a new local token, almost like a “Medellin Coin,” that could help local startups get funding. As of now they’re calling it the “Innovation Token” and target October for its debut.

Another hope that Colombians have for blockchain: solving the problem of identity. No one likes dealing with government paperwork, but in Colombia it’s a bigger headache than in the U.S. “For health care they ask you for 10 items of identification. In the tax office, they ask you for 20,” says Susana Arrieta, who works for the Colombian branch of NEM. She says that filing taxes is so bewildering and complicated, that “normal people have to hire accountants. We don’t make a lot, and we have to hire accountants to pay our taxes. Everything is manual. They must change it.”

“Putting in the work.”

With bitcoin, every 10 minutes, miners compete for a reward of 12.5 bitcoins. (At least this is the reward until May 26, 2020, when it will halve to 6.25 coins.) The miners keep 100 percent of the reward—that’s their incentive to keep chugging away at the world’s most controversial math homework, and this, of course, is the process that confirms the transactions and keeps the bitcoin network secure.

Dash works differently. Miners keep 45 percent of the reward, and 45 percent goes to the masternodes, and 10 percent goes to the Dash Treasury.

This treasury is a pool of capital that can be deployed to fund worthy projects. Teams can submit proposals to Dash on how to spend that capital—much in the same way how, at a corporation, the different divisions vie for how to spend the firm’s money.

And this brings us back to that surprising glut of Dash meet-ups. Thanks to the capital from the Treasury, George Donnelly has a budget to pay a team of 40 freelancers to go door-to-door and get merchants to accept Dash. So far they have 315 merchants in Colombia, most of them clustered in Medellin. It’s old-school retail marketing. They’re not hoping that Dash will grow organically. They’re not relying on word of mouth.

“We’re putting in the work,” says Donnelly. “Most people in the crypto space are not. It’s all fancy conferences; it’s castles in the sky.” His team says that 1,422 Colombians have Active Dash wallets—95 percent on Android, five percent on iPhone. (Donnelly says that most of their demo can’t afford iPhones; “Android is the everyman’s phone.”)

This helps explain why the CoinLogiq ATMs include not just bitcoin, but Ethereum, Litecoin, and Dash. “Here on the ground, we don’t have any competition,” says Donnelly. “Compare the efforts with Bitcoin Cash. They don’t have a treasury. They spend all their time fighting and dragging the whole ecosystem down.” He looks at me intently. “Everyone else is wrapped up in the cruises and the conferences—here we’re working on the streets of a developing nation.”

That might be true, but after poking around for a few weeks, I found that most of the random Colombians I talked to in Medellin—taxi drivers, tour guides, bartenders—had not heard of Dash. (In fairness to Donnelly, his team has only been pounding the pavement for a few months—it’s early.)

The bear market isn’t helping. On Crypto Twitter, you often hear the refrain that price is irrelevant and that we’re focused on building. That’s an admirable position, but I’m skeptical. In January 2018, each Dash was worth $1,338. As of publication, that has cratered to around $80. “The price has affected things,” Donnelly concedes. “Every time the price of Dash falls my purchasing power reduces.” He says that for now the price decline is “manageable” but has slowed the growth, and adds that “some merchants have begun to complain.”

Yet there does appear to be real growth. Thanks to the sneakers-on-the-ground approach, Colombia now has the third most Dash merchants of any nation. More generally, Colombians are using crypto at a higher clip than you might expect. A representative from Coin Dance, which tracks the statistics of transactions on Local Bitcoins, told me that Colombian Pesos to Bitcoin is the seventh most common currency paring. (The top 10: Russian Ruble, Venezuelan Bolivar, U.S. dollar, Nigerian Naira, Chinese Yuan, British Pound, Colombian Peso, Euro, Indian Rupee, Peru Nuevo Sol.)

Merchant adoption is just one piece of the puzzle. Thousands of Venezuelans have crossed the border into Colombia, and many of them need to send money back to their families. Dash wants to be the go-to solution for remittances. One meet-up advertises: “Aprende como mandar dinero rápido y bato a Venezuela, y puedes recibir $30.000 COP en Dash para mandarselo a tu familia,” or (via, um, Google Translate), “Learn how to send fast and cheap money to Venezuela, and you can receive $30,000 COP in Dash to send to your family.”

Which gets us back to Venezuela.

Crypto: The stable asset

Two years ago, Eugenia Alcalá, the psychologist, had a health problem that forced her to miss work, and when she was ready to return, she didn’t want to earn her income only in Bolivars. The hyperinflation was crippling. At first she tried to earn income in U.S. dollars, but says the Venezuelan government made this tricky. She was not allowed to have a bank account outside her country, she had no non-Venezuelan credit cards, and no way to get her PayPal account verified.

As compelling as these use-cases are, something still bugged me. Do all of these “unbanked” people really have smartphones, which you’d need for crypto?

So she began exploring crypto. Bitcoin was obviously a possibility, but she was drawn to the governance model of Dash—where 10 percent of the mining incentives go to the Treasury, which, theoretically, could be spent to build an ecosystem in Venezuela. She submitted a proposal to the Dash Treasury, and within a month they greenlit a budget. Other Venezuelans have done the same thing: Alejandro Echeverria and Lorenzo Rey are leading separate evangelist teams within the Dash community, and there are now 2,427 Dash-accepting merchants in Venezuela—nearly 10 times as many as there are in the United States.

As compelling as these use-cases are, something still bugged me. Do all of these “unbanked” people really have smartphones, which you’d need for crypto?

It turns out that most of them don’t. Rey says that only 40 percent of Venezuelans own smartphones, so his team cobbled together a workaround: text-based crypto, or “Dash Text.” Over a Skype video call, Rey and Echeverria give me a demonstration of how it works, holding up two old-school phones. By texting “Equilibrar,” you immediately get a reply with the balance of your Dash account. I watch as Echeverria zaps a text to Rey, whose phone instantly gets a new text message: Dash received. You can send crypto in under two seconds. The menu system might be a bit clunky, like the voice dial-up “movie phone” from the late ’90s, but it seems to work.

Dash Text could be especially useful for remittances. “There are 300,000 Venezuelans living in Florida alone, and almost all of them send remittances back home,” says Echeverria. “Dash Text could be a way to do it.” At the moment this crypto-text is only functional in Venezuela, but they have plans to expand to Nigeria and India—countries heavy on remittances, light on smartphones. They’re working on integration with WhatsApp and Telegram. The Dash team says that in the first month it was available, 3,261 Venezuelans have used the texting system. They will soon begin a marketing push (recruiting local influencers on social media) to broaden its reach.

Embracing the same door-knocking strategy as Donnelly in Colombia, Dash Venezuela is not waiting for adoption to occur “organically.” They’re impatient. The stakes here are real. Again funded with capital from the Dash treasury, a team of reps gives the Venezuelan merchants one-on-one lessons, they install the POS (no hardware required), and they sweeten the deal by giving the merchants free publicity. (Example: A sandwich shop gets effectively “advertised” when Dash gives it a shout-out.)

“But aren’t the merchants skeptical?” I ask Echeverria and Rey. “What’s their usual push-back?”

“The first question merchants ask is, ‘Is this legal?’” says Echeverria. Ironically, the government has—perhaps inadvertently—soothed those fears. The creation of the Petro (Venezuela’s state-backed cryptocurrency), for all its controversy, “established a completely legal framework for cryptocurrencies,” as Echeverria sees it. Thanks to Petro, Venezuelans citizens now have a greater fluency of cryptocurrency; for example, Echeverria says that when he logs into his bank account, he sees his balance in both Bolivar and Petro.

Dash has recruited not just the oddball cafe and mom-and-pop shop, but franchises like Subway, Papa Johns, and Re/MAX real estate. They are focused on what they call “essential merchants” like mini-marts, restaurants, and car repair joints.

“Once you put your money in Dash, you are protecting your Bolivar,” says Echeverria. Imagine taking your U.S. paycheck and socking it away in crypto—just to keep it safe. From the standpoint of ordinary Venezuelans, in a weird sense, 2018 was still a bull market—every day, Dash buys more Bolivars.

Not only does hyperinflation do things like make it hard to buy a gallon of milk or your bus ticket home from work, it also causes some frustrating—if not devastating—practical difficulties. Think about the mechanics of an ATM. When the Bolivars plunge in value, even a small withdrawal requires a cartoonishly tall stack of near-worthless paper. This problem has Coinlogiq’s attention. “If you withdraw $5 [U.S. dollars] worth of Bolivar in Venezuela from an ATM, you’ll probably get a message saying they’re out of currency,” says Golden. “How many transactions can you get each day? The ATM model doesn’t work.” So Coinlogiq designed a new model of ATM just for Venezuela, called the ‘Gladiator,” that will be linked to local banks. “You withdraw crypto, and it will automatically send the Bolivar to your bank,” he says, eliminating the need to pump out hundreds of slips of paper.

Alcalá is surprised—even amused—that other corners of the world are even thinking about adopting cryptocurrencies. What’s the point? (She’s basically agreeing with my U.S. friends.) “Normal people do not need the cryptocurrencies as urgently as we do,” she says. “Normal people are satisfied with their economies. They don’t feel that banks or centralized organizations have any real problems, because their services are doing good enough. But Venezuela is the perfect storm for cryptocurrencies.”

When I finally left Latin America, I headed back to the U.S. for a trip to see my family and friends, and I swiped my Visa card without blinking. I used the ATM. I have absolutely no need to spend any cryptocurrency. For ordinary Venezuelans? I think back to something Alcalá told me, that one of her teammates said that thanks to cryptocurrency, “for the first time I can remember, I’m not afraid that next week I won’t be able to afford to buy groceries.”

Photos by Jeff Wilser. Wilser is the author of The Book of Joe: The Life, Wit, and (Sometimes Accidental) Wisdom of Joe Biden. Follow him on Twitter.

Update: This article originally misspelled the name is the director of Blockchain Centre in Colombia. It’s Felipe Cano, not Canon.