Seven Russian intelligence officers are being charged with hacking, conspiracy and disinformation, the Department of Justice announced last week. They were part of an international operation spanning from 2014 to 2018, which targeted anti-doping organizations in the US, Canada and Europe, in retaliation for Russian athletes being caught doping in the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Though the ins and outs of the affair can be confusing, there’s one relatable part of the story: the sheer pettiness of assigning a team of spies to target the staff of an organization you don’t like, because they caught you cheating and you couldn’t handle it.

You might think Russia, a global military and economic power, would have bigger fish to fry. You might think the right response to its athletes being caught doping would be to put more money into training programs, and tell the spandexed Olympians to ease up on the drugs. But no, I’m sorry—you’re not thinking enough like a Russian agent. Because in revenge for being banned from this year’s winter Olympics, the Russian military intelligence service, or GRU by its English acronym, responded with some Mean-Girls-meets-Mr-Robot shit.

Full details are in the indictment published this week by the DOJ, which is worth reading just to understand the lengths that the agents took to get even with the people who caught their national squad cheating. But if you don’t have the time to go over 40 pages, here’s how it went down.

First, the GRU mined its own bitcoin to fund some of the operations anonymously. Previous investigations into Russian hacking have exposed the same crypto-powered strategy: the coordinated hacking of Hillary Clinton and the DNC’s emails in 2016 was financed by a web of cryptocurrency money laundering, and bitcoin has also been used by GRU agents to pay intermediaries (like Romanian domain registries) for services.

In this case cryptocurrency was part of the phishing campaign. Agents used bitcoin to rent servers and purchase domains like “wada-arna.org”, which would impersonate the World Anti-Doping Agency’s real website, wada-ama.org. With duplicate sites set up, the agents used email phishing techniques to trick officials from the WADA, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), soccer governing body FIFA, and others, prompting the users to type their credentials into spoof mail login or password reset pages.

This is the kind of thing you can do from a computer terminal anywhere in the world, so is not a huge deal on the pettiness scale, but things got much more intense.

As a next step, the GRU sent “on site teams” to hotels around the world where they knew that WADA officials would be staying. These teams took specialized hardware with them—the indictment doesn’t say exactly what—and used it to exploit vulnerabilities in the hotels’ wifi networks, which could be used to steal access credentials from the officials’ computers when they logged on.

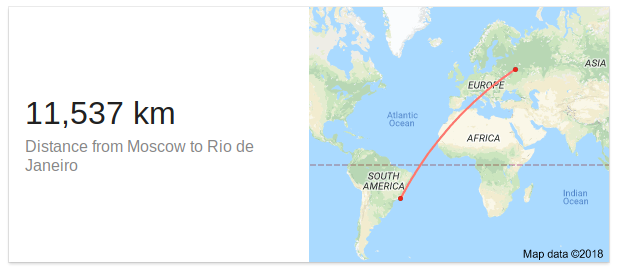

To reiterate: the Russian agents tracked the movements of these officials, whose only job was to stop athletes using drugs; sent agents from Moscow to as far away as Rio de Janeiro to stay in the same hotels as them; and used specialized equipment to compromise the hotels’ internet infrastructure, just to get even with the people who caught the Russian athletics team when the athletes were the ones cheating in the first place.

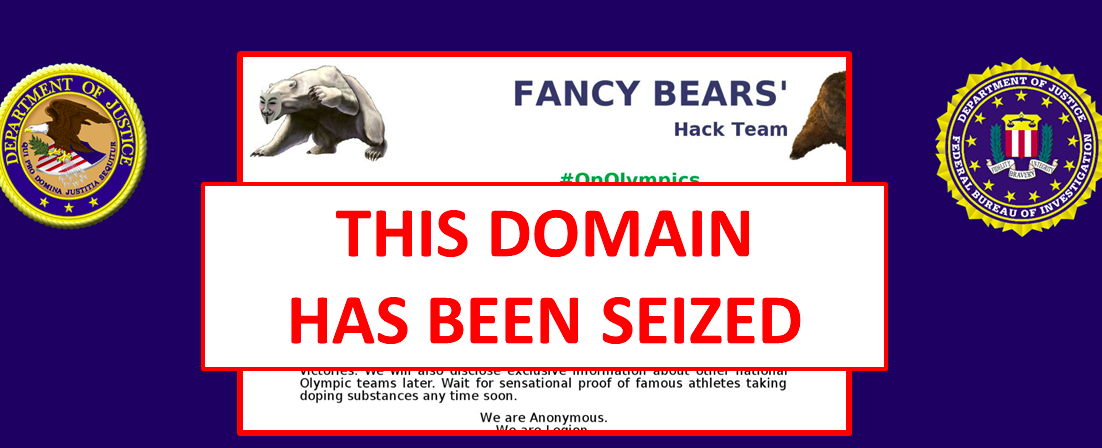

Already this is outrageously petty, but just hacking these officials’ computers was not even the end goal. Once they were able to access the anti-doping groups’ data, the Russian operatives downloaded medical information on over 250 athletes, and set up a publicity campaign to leak it to journalists under the alias Fancy Bears’ Hack Team. Posing as hacktivists who wanted to expose doping in sports, the Fancy Bears sent out documents to the media which they alleged showed widespread drug use—except some of the documents had been altered to show incorrect information, which they hoped would be attributed to WADA, FIFA and others.

It was an extremely elaborate, extremely petty ruse.

The goal of the campaign was to “undermine, retaliate against and otherwise delegitimize the efforts of international anti-doping organizations and officials who had publicly exposed Russian government-sponsored doping,” the indictment says. In other words it was a huge, convoluted revenge scheme which they nearly got away with. It’s kind of amazing that Russian military intelligence would give this kind of task to their operatives, but then maybe we can all see something of ourselves in Aleksei, Evgenii, Ivan, Artem, Dmitriy, Oleg and Alexey (the alleged agents named in the indictment).

The men in question are all believed to be back in Russia, so have approximately zero chance of actually being brought to trial for any of this. And of course the Russian government denies the allegations anyway, just like it denies more serious charges like hacking the UK Foreign Office and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

In conclusion: Russian intelligence agents hold grudges and are extremely petty.