A quick history of civilization:

1215: The signing of the Magna Carta

1776: The signing of the Declaration of Independence

2015: The establishment of Liberland, the world’s first country powered by a blockchain

I want to learn more about this next chapter of civilization. So I’m here to visit Liberland, a tiny island between Croatia and Serbia. The island is about the size of Harlem. In something of a diplomatic quirk, neither country really wanted the land, and for years it languished as barren, unclaimed territory. (The short version: The border between the two former Yugoslavian countries isn’t a straight line, but a disputed zig-zag, and if Croatia or Serbia “claimed” the island, that would, paradoxically, endorse a definition of the borders that would lose territory elsewhere. The island was a consolation prize no one wanted.)

Then someone claimed it. In 2015, a young Czech named Vit Jedlička declared that the island would, henceforth, be known as Liberland, that it would be founded on libertarian principles, and that anyone who wants to join is welcome. Oh, and it would govern itself on a blockchain. There are now 560,000 residents, or rather e-residents.

I had visions of rowing a canoe across the Danube river, docking on the shores of Liberland, and then walking on the very soil that will, one day, give birth to this new utopia. I would meet the brave men and women who are setting up the tents and huts, like modern day Pilgrims. I would tell my grandkids. I would preserve the soil for posterity, or maybe I’d sell it on eBay.

How to get there? I attend a crypto meet-up in Belgrade—about 120 miles away from the island—at a bar called the Miner’s Pub. Over craft beers I ask how to get to Liberland.

The island is empty wilderness. There are no airports or homes or bitcoin ATMs.

“Can I fly into it? Is there an airport?”

Some chuckles. No.

“Can I drive?”

No.

“Can I take a boat?”

I can’t really do that, either. The island is empty wilderness. There are no airports or homes or bitcoin ATMs. In fact, the border is now guarded by the Croatian military, and a stint in prison is just beyond my appetite for gonzo journalism.

“But you should meet with Serbia’s official Liberland representative,” someone tells me.

Game on.

Homeless Ambassadors

This Liberland ambassador is a 27-year-old named Daniel Dabek. He also runs a blockchain company called SafeX, the largest crypto startup in Belgrade.

So how does one become an ambassador to Liberland?

In 2013, Dabek was homeless, living in the trees and bushes of Presidio Park in San Francisco. Every night he found a newspaper, spread it on a patch of dirt, and used that as his bedding. People tossed him cash. When he needed to shower, he would pay $7 to use a nearby gym.

Dan Dabek

Dabek began day-trading stocks when he was 15, made $70k by the time he was 18, matriculated to Fordham, and then dropped out of Fordham. In 2013, he bought 10 bitcoin when they were $100 a pop. So in San Francisco, he slept in the park to save money, confident that his bitcoin would eventually explode in value. If he sold his bitcoin to pay rent, he wouldn’t enjoy the eventual 10X or maybe 100X. He clung to those 10 bitcoin like Gollum and his Precious. “I hodl hard,” he tells me now.

Dabek has the boy-ish face you’d expect from a 20-something crypto-prodigy, along with the obligatory gray zip-up sweater. “After the forest, I lived in a ‘Bitcoin Hotel’ in San Francisco,” he says. The apartment was on Mission Street and home to other crypto-enthusiasts. Dabek attended bitcoin meet-ups where he rubbed elbows with Vitalik Buterin and the like.

In 2015, he heard about an enchanted place… a magical island called Liberland. A new nation. A nation that is completely free. A nation built on a blockchain.

“This was huge news,” he says, speaking quickly. “Epic news. At that time, everything was happening. The Mt. Gox hack. Ethereum ICO. And now people are building countries!”

So he packed his bags and moved to Europe.

“Knocking on the door is interruptive,” he explains. “I prefer asynchronous communication.”

His original plan was to move to Liberland, or as close as he could get. The nearest city? Belgrade. “I thought I would move to Belgrade to sort of get settled, and acclimate myself,” he says, like how you spend a few weeks in base camp before hiking Everest. He initially assumed that Liberland was livable, and then, like me, realized it wasn’t quite ready for prime time.

Meanwhile, Dabek did some consulting work, kept trading and coding, and had his own idea for a blockchain company: a “decentralized, peer-to-peer marketplace,” or basically Amazon meets eBay meets blockchain. This is the idea that would become SafeX, listed on CoinMarketCap with a market cap of $7.3 million (the 361st in size), at the time of publication.

Dabek gives me a tour of the SafeX offices, which pull double-duty as the headquarters of Liberland in Belgrade. One wall displays a SafeX logo, another wall a Liberland flag. The door to Dabek’s office has a hand-written note that says, Do Not Knock. Write on Slack or Text Message First. “Knocking on the door is interruptive,” he explains. “I prefer asynchronous communication.”

I’m reminded that he’s only 27, and he’s now the leader of a company with approximately 25 employees . Prior to this, most of his time has been spent trading, coding, or sleeping under trees.

“How’d you learn to be a manager?”

“I prepared for this by watching movies,” he says as he continues the tour. “The Aviator. The Social Network. There Will be Blood.” It’s not clear if he’s joking.

Dabek soon met Vit Jedlička in the crypto circles in Belgrade, the two hit it off, and he was tapped to be the official representative of Liberland.

But here’s what I really want to know: What will Liberland actually be like? Why does Dabek care about it? How will it work as a fully functioning society? How will living in Liberland be different from living in, say, Nebraska?

“When I cross the border, I want a guarantee that I’m not going to be searched,” he says. “If people want to smoke pot in Liberland, that’s totally acceptable.”

Fair enough. But that’s not particularly unique these days. Where will people live? What will Liberland neighborhoods look like? “People will have their land, and they can develop what they can afford to develop,” Dabek says. “Some people will have their own house, or their own tent, or their own hut.”

“A bit like Burning Man?”

He rolls his eyes. “This is a little bit more serious. Building a country is so freaking hard.”

The Meritocracy

Another guy who knows how freaking hard it is: Vit Jedlička, the 35-year-old President of Liberland. (“I’m still the youngest president,” he tells me, laughing.) He’s not in Belgrade at the moment (he’s based in Prague), so I catch him on Skype video—he talks to me from the back of a cab. His Skype status reads, “Setting up Liberland.”

“I don’t think Liberland should have a state-owned hospital,” Jedlička says, as he trusts the invisible hand of the market. There are already six applications from private companies that want to build hospitals or provide medical solutions, according to the President, and that “they don’t need any subsidies, and they actually don’t even need any approval in Liberland. That’s great for them, because they can avoid a lot of hassles.” If you build it, they will come.

On Liberland.org, the forums provide some anecdotal evidence that back Jedlička’s logic: aspiring Liberland citizens seem to be willing, and eager, to fill the medical void. The thread “Doctor in Liberland?” Includes posts like:

- I am an advanced nurse practitioner in acute medicine. I would be useful in this exciting new democracy!

- Hi i am a psychiatric practician… Liberland will probably need one …

- If You guys need dentist just let me know.

(Then again, I didn’t see threads with volunteers for the less glamorous parts of a functioning society: trash collectors, toilet scrubbers, blockchain journalists.)

Jedlička claims they’ve already snared $32 billion of private money for investment.

What about urban planning? Once again, Jedlička trusts the free market. In 2016 they held a global architecture competition, and the winning design envisioned a bright green, futuristic island that looks like a city from Avatar; it’s a “horizontal city” stacked vertically—imagine a park stacked upon a park stacked upon a park. Another design featured skyscrapers that soared three km high, and another showcased a “massive, hexagonal tube-shaped geometrical structure resembling a spaceship, with an airport on the highest level,” as Liberland Press described.

Who pays for all of this?

The free market, the free market, the free market. Specifically, Jedlička claims they’ve already snared $32 billion of private money for investment. This a staggering figure.

“Did I hear that right?” I ask. “$32 billion?”

“It’s a pretty crazy number,” he acknowledges. (Later, I would email him to triple-check that I heard this accurately. He confirmed that yes, there is $32 billion, with a B.) If true, that’s enough capital to build a replica of Apple’s fancy new campus…and then build five more. Or they could build a replica of One World Trade Center…and then build seven more. A $32 billion piggybank is absolutely insane.

“We’ve got a bunch of billionaires that applied for citizenship,” Jedlička explains. “We just need to formalize it a little bit before we present it, and make sure that we actually sign the contracts with all of these people.” (Jedlička declined to disclose most of the names.)

Vit Jedlička, president of Liberland

Liberland has a merit-based economy. Literally. The Merit is the nation’s unit of currency—now listed on the Altilly exchange as “LLM”—and each Merit is pegged to the U.S. dollar. Want to become a Liberland citizen? It will cost you 5,000 merits, or $5,000. If light on cash, you can earn merits “through efforts in similar value,” although it’s not crystal clear to me how that works. As of April 2019, there are currently 800 citizens (it’s unclear how many of them contributed $5k. I asked this of Jedlička, and he replied, “all have substantially contributed to the creation of the country.”)

The key difference between e-residency and citizenship is that you can vote as a citizen. The more taxes you pay, the more you vote. (One could argue that this is Citizens United on steroids.) I ask Jedlička if he sees this as at all problematic. Not at all! “Wouldn’t it be great if there are some rich people that pay the taxes for everybody else?” he asks. “And [everybody else] can enjoy the fruits of it? I think that’s pretty cool.”

Fine Dining

Back at SafeX headquarters, Dabek says he’s hungry. “Are you hungry?” he asks me.

“Sure.”

We take a walk, and I’m curious where this young crypto-mogul will lead us for a snack. Belgrade has excellent food. I’ve grown fond of the kobasice (sausage) and musaka, which is kind of like lasagna but stuffed with meat and potatoes.

“Is McDonald’s okay?”

This is not a joke and we head to the Golden Arches, where we both order Chicken McNuggets to go, and bring them back to the SafeX offices. Dabek was frugal as a homeless guy and he hasn’t really changed, despite a poster-size photo in his office that shows him standing next to a green Lamborghini. “I don’t have a Lambo because I don’t like cars, and they depreciate,” he says. (He drives an Audi X.) “The people who are like that [the Lambo seekers] are the scammers, the wheelers and dealers.”

You can’t just create a club and say it’s a nation—you have to display legitimate signs of a community, a culture, a shared identity.

Dabek shows me some local newspaper clippings that covered a Liberland anniversary party. “We had eight ships with 250 people,” he said proudly.

I notice that Dabek often says “we” when talking about his fellow Liberland countrymen. We believe in freedom. We want to be recognized by the U.N. I ask him if speaking in the first-person, as a Liberland citizen, is a conscious choice.

“It is,” he says. A year ago, he asked his attorney to research the viability of Liberland’s quest for nationhood. The lawyer sent him a two-page memo. The document outlined the problems the lawyer had flagged, and one obstacle is that you can’t just create a club and say it’s a nation—you have to display legitimate signs of a community, a culture, a shared identity. This is why Dabek now says “we.” This is why he shows me a Liberland passport, which looks just like an ordinary passport. It’s also why Liberland now has organizations like the Liberland chess team, a Liberland kayaking club, a Liberland Chamber of Commerce, a Liberland Aviation society, and Liberland Brewers. There’s a Liberland beer.

“What else did the lawyer say in his memo?”

Dabek pauses, thinks, and then declines to elaborate.

One item that was almost certainly in that memo is the current state of Croatia and Serbia relations. The president of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, does not recognize Liberland. (Almost no one does.) Jedlička says that he has a receptive ear in the head of the Croatian opposition party, Zoran Milanović, so he’s biding his time until a potential change in leadership. Yet there’s a more existential threat: The entire “unclaimed” status of Liberland exists only because of the border dispute between Croatia and Serbia. If they make nice and resolve that dispute, Liberland could get squeezed out of existence. (Jedlička insists that his claim should stand regardless.)

To join the United Nations, Liberland needs official recognition by five sovereign states. Currently they have zero. (Their biggest diplomatic triumph, to date, is recognition from Somaliland.) “We’re working quite hard with U.S. diplomats,” says Jedlička. Jedlička briefly met Mike Pence at a dinner, and he’s bullish on Trump’s stance on Liberland. “It’s going to be a friendly relationship,” Jedlička predicts, noting that Trump’s first wife, Ivana, was also from Czechoslovakia, just like him. “[Trump] is a supporter of liberty in many aspects. He’s a businessman. So I hope he will decide to build something extraordinary in Liberland.”

“I vote for 14.”

Liberland will govern itself through the blockchain. When I speak to Jedlička a second time, he had just returned from an EOS conference in Norway, where he secured a partnership with EOS, which Liberland will use for things like arbitration. Let’s say there’s a dispute about whether “Bob” stole Merits (the coin of the land) from “Alice.” The case will go to arbitration, and if Bob is found guilty, then the EOS smart contracts will instantly deduct the balance of Merits from Bob’s account.

True, that does sound like a tidy way to handle the mechanics of arbitration, but who are the human beings handling these cases? Who’s the judge and jury? What’s the court system like?

A boat envisaged for the waterway

Many of those pesky details have been hammered out in Liberland’s Constitution, available for all to see right here. Yet utopias are never unanimous. Rules beget dissent. In just one tiny example of how tricky this can be, the second draft of the Constitution contains the line, “No law shall prohibit video and/or audio recording of any agent of the Public Administration in public space and whilst on duty.”

Not so fast, said the Liberland Press. Acting as something of a watchdog, Liberland Press evaluated the document and asks, “Why only when they are on duty? Should not all citizens, residents and visitors have the right to film and record whatever they want in public view?” (The blog post is titled, “Liberland’s Constitution: Is It Libertarian Enough?”)

And then there’s the uglier stuff. How should an aggressively free-market society handle the more sensitive issues like, well, sex? Age of consent? A 2015 Forum post asks, “Pedophilia in Liberland?”

Some responses:

- Mliber: No.

- D99: I think the minimal age should be 16 years. We are civilized people, not some barbarians.

- Ash: I agree with 16.

- JimPius: 16 sounds to be okay.

- Parmalat1184: I vote for 14.

Blockchains can only do so much. The tougher issues, as always, will need to be resolved by humans.

In terms of human capital, Liberland has roughly 130 representatives (such as Dabek) around the world, as well as seven advisors, four Ministers, and, oddly, two Vice Presidents. There are nine people working on Liberland full-time, but for most participants, the founding of this nation is something of a side-hustle. Every Tuesday at 9 a.m. Liberland time, Jedlička has a conference call to review progress.

Why shouldn’t we choose to live in a nation of like-minded people? Why be a slave to geography?

Jedlička isn’t blind. He knows that given the diplomatic impasse with Croatia, it could be years before the island can become his home. He’s not waiting that long. The Liberland team is creating something of an armada, full of house boats, that can function as a floating city near the island. He’s also planning settlements on the Serbian side of the border. A Belgrade-based architect, Marija Blesic, who’s also a co-founder of SafeX and an organizer of crypto meet-ups, is designing the interior of Liberland’s new flagship boat, called Bitcoin Freedom. “It’s in the shipyard right now,” she tells me. “They’re painting it. It will have tons of cabins, a place for co-working, a kitchen, a bar.”

Jedlička is skilled at recruiting allies, and one of them is Petar Čekerevac, an economist who works at a Belgrade-based organization called Libek, a libertarian think tank. “Serbia is a country that used to be a free market before World War II, and it was doing relatively okay,’” he explains to me, as we sip fruit juice at a Belgrade cafe. “World War II completely destroyed the country. Then the communists overran the system, and it was a command economy for 45 years.” In the ’90s, Serbia fought three wars in 10 years. “We had the biggest hyper-inflation in the world,” Čekerevac continues. “We’re way behind.” He ticks off the problems facing the Serbian economy: government corruption, oppressive taxes, a bloated bureaucracy that makes it tough to start a business.

Given that perspective, it’s easy to see the appeal of Liberland to Serbians like Čekerevac. “It’s super interesting to see a utopian country being formed on Libertarian principles,” says Čekerevac. “As usual, it’s based on socialism.”

Jedlička asked Čekerevac to try and calculate the economic benefit to Serbia and Croatia of having Liberland—an economic “free zone”—next door. (Much of Čekerevac’s academic research has focused on the upside of economic free zones, like the ones established in China.)

“It’s common to view off-shore countries as a place where money flows to, but research shows that when money goes off-shore, it comes back in the form of investments to the base country,” says Čekerevac. When he crunched the numbers, his model showed that because Serbia and Croatia would export goods and services to Liberland—steel, lumber, plastic—this would boost the GDPs of both countries to the tune of “thousands, per capita, over the next 10 years.”

He also adds a note of caution. “Whether it’s going to happen, I don’t know. You have so many constraints. Are Serbia and Croatia going to resolve their issue? What is the EU going to say? What is the US going to say? There are a lot of questions.”

It’s easy to make light of this quixotic tilting at windmills, but you can also find something earnest, and even noble, in the quest. Most of us are patriots by geographic fluke. We salute a certain flag or speak a certain language because of where we happened to be born, just like how we don’t really “choose” our football or basketball teams. Jedlička wants to upend this framework, a model that is literally as old as civilization itself. Why shouldn’t we choose to live in a nation of like-minded people? Why be a slave to geography? “The textbooks are completely wrong,” says Jedlička, explaining that the textbooks say that “language, or the color of the skin, or the [geographic] territory are the defining things for the nation. We know very well that the strongest, most defining aspect is the belief in freedom. The United States of America was founded on that idea.”

Before I leave the SafeX and Liberland offices, Dabek hands me something. “You should have these.”

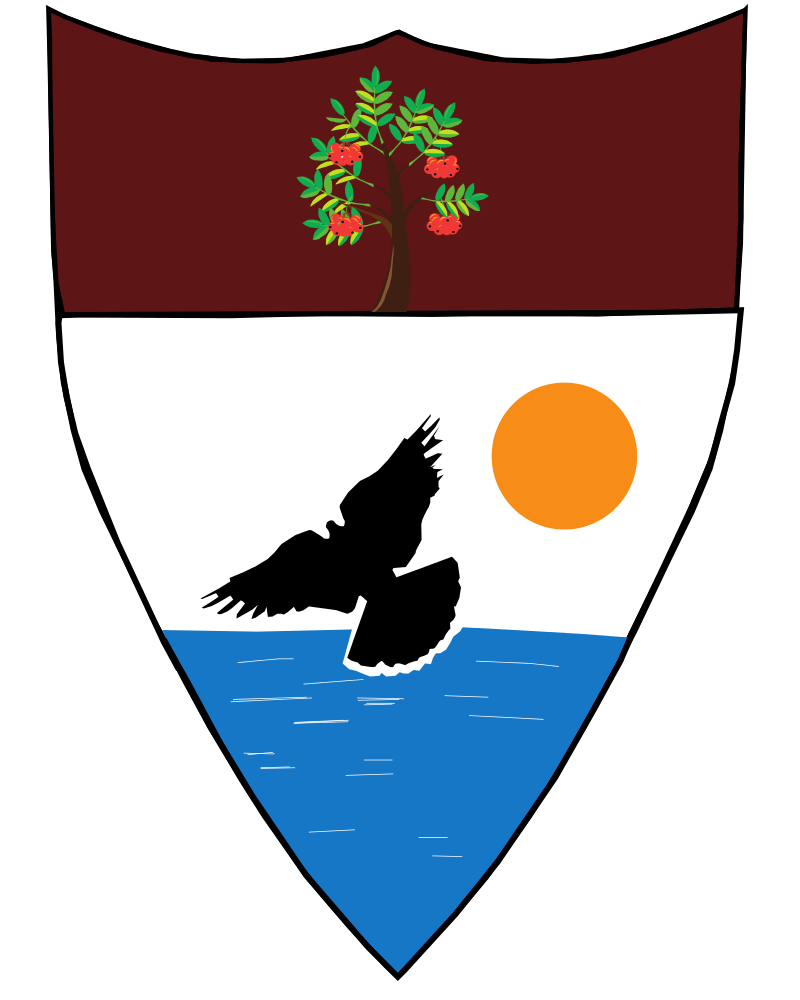

He hands me a collection of pins. They look like the kind of “American flag pins” that politicians wear to prove they’re tough on terror. They’re pins of the Liberland flag.

I try to decline—journalists don’t accept gifts—but Dabek insists and I feel rude leaving them on the table. So I now have an official Liberland flag. On a lark, just to see what it’s like, I fill out the registration form to become a Liberland e-resident. It takes two minutes.

Maybe, some day, I can take a flight to Liberland and experience the glory of unfettered free markets.