We have been told by privacy advocates and technologists that financial anonymity is important.

We’ve been taught that the information we emit when we make purchases can be used by the government to increasingly surveil society. And these same advocates have made us aware that banks and tech companies are doing whatever they can to strip us of our financial anonymity in order to push more goods and services on us.

But for most of us, all we really want is a convenient option for making payments. We’ll take whatever degree of anonymity that happens to come with that option.

Take good old fashioned cash, for example. Making in-person exchanges with banknotes is still the best way to get financial privacy. But the average cash user doesn’t care very much about cash’s privacy. Lured by the convenience of cards, people across the globe are choosing to make more and more non-cash—and thus non-anonymous—payments.

Sweden is at the forefront of this trend, conducting just 12-13 percent of its retail payments using kroner banknotes and coins. Swedes don’t seem to be too bothered about the trend towards non-anonymous trade. Sweden’s central bank—the Riksbank—recently asked citizens what they thought about the decline in cash usage. Seventy three percent of respondents were either positive or ambivalent, with only 27 percent seeing it as a negative thing.

All we really want is a convenient option for making payments. We'll take whatever degree of anonymity that happens to come with that option.

In 2016, the Reserve Bank of Australia—Australia’s central bank—asked Australians to list their most important reason for using cash. Respondents ranked privacy ninth. The most popular reasons for using banknotes included broad merchant acceptance, the desire to avoid card surcharges, speed or ease, budgeting, and the ability to enjoy cash discounts.

Australians aren’t alone in being apathetic about privacy. That same year the European Central Bank asked Europeans the following question: “what are the two most important advantages of cash for payments?” Only 13 percent of survey respondents listed anonymity as one of their two options, placing it sixth. The most important advantages were providing a clear overview of expenses (42 percent), always accepted (38 percent), fast (32 percent), and easy (21 percent).

Within Europe, no country is more cash intensive than Austria. An incredible 82 percent of all retail payments are still made with banknotes and coins, credit cards clocking in at a measly three percent and debit cards at 11 percent. But even cash loving Austrians rank anonymity pretty low. In a recent survey run by the nation’s central bank, Austrians who tend to rely more on cash than cards were asked to assess the importance of different properties of payments instruments. Anonymity came in sixth, after other features like speed, “does not involve extra costs such as account maintenance fees”, ease, efficiency, and “provides a clear view of my expenses.”

These survey results tell us people value banknotes not for their privacy, but because they are fast and easy to use. A simple glance into their wallet tells people how much they can spend, thus providing an easy way to budget. I can’t help but wonder whether people would care if each banknote had an RFID tag on it that tracked purchases.

If we don’t really care about anonymity much to begin with, various carrots and incentives provided by non-anonymous payments networks can lead us to desert anonymous payments methods all the quicker.

Card networks like Visa and MasterCard use rewards to steer people away from choosing financial privacy. Take the choice that a consumer faces between using anonymous cash or a rewards card to buy $100 in groceries. Paying with cash only nets $100 in groceries, but with the credit card the consumer gets the $100 in groceries and $2 cash back. No wonder so many people are choosing to pay with credit cards instead of cash.

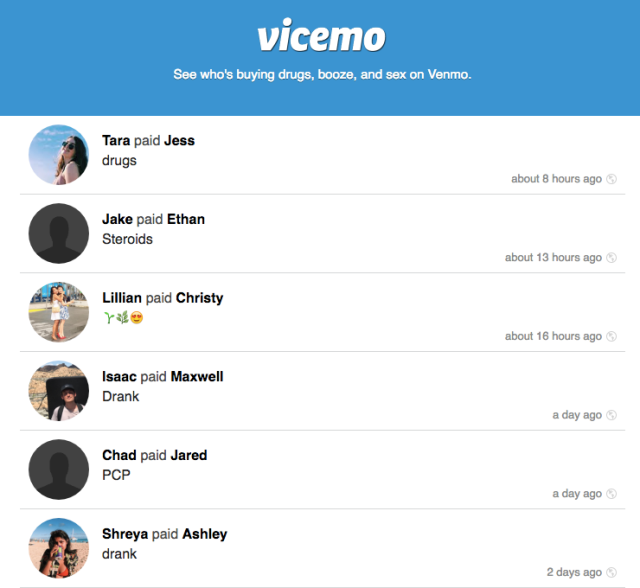

Venmo, a popular person-to-person payments app, also shows the effectiveness of these carrots. Venmo posts details of the payments that users have made to a public feed. Users can opt out by choosing a private option, but many choose not to. For a taste of what that looks like, check out Vicemo. It pulls Venmo transactions involving drugs, booze, and sex and makes them visible for everyone to see.

Lack of privacy does not seem to concern Venmo users. In a survey of frequent mobile payments app users, researchers from the University of Washington found that only eight out of 106 respondents chose to avoid using Venmo because of its lack of privacy. Out of 80 Venmo users, the same researchers found that 88 percent of respondents indicated indifference towards whether their transactions were shared or private. In interviews with 14 Venmo users, researchers found that a user’s decision not to share a given transaction was less about protecting their own privacy and more about not “clogging others’ feeds with mundane posts.”

Why are Venmo users so willing to give up their privacy? Venmo is fun. People like to see what their friends are doing. Even if people care about privacy, it only takes a small carrot (like amusement) for them to give it up.

Over the past month [on Zcash], 83,305 transparent transactions have been made whereas only 1263 fully shielded transactions were made.

In addition to the incentives provided by non-anonymous payments options, privacy-promoting forms of payments are often plagued by self-inflicted problems such as poor user experience. Take cryptocurrencies, for instance, the newest pulpit for privacy advocates. Whereas cash’s anonymity is extremely well-integrated into its design—there is no need to toggle a button or learn a special routing technique to anonymize a cash payment—attaining anonymity with cryptocurrencies is an awkward process. All bitcoin transfers are transparent—every transaction is written onto a publicly-available ledger. But it is possible to turn on bitcoin’s privacy by avoiding exchanges that require identification, using coin mixers, and not reusing addresses.

But that’s a lot of extra steps. It’s not very surprising that in its 2017 Bitcoin Omnibus Survey, the Bank of Canada found that only three percent of respondents said that they owned bitcoin because it “allows me to make payments anonymously.” At the top of motivations for holding the stuff was “it is an investment.”

Or take Zcash, a cryptocurrency that uses zero-knowledge proofs to fix some of the deficiencies in bitcoin privacy. Users have the option to use a transparent Zcash address or a shielded one. Like a regular bitcoin payment, Zcash’s transparent payments are recorded on a public ledger. But shielded addresses are hidden.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

Zcash’s privacy option has not proven very popular. Over the past month, 83,305 transparent transactions have been made whereas only 1263 fully shielded transactions were made. A fully shielded transaction occurs when a user with a shielded address sends Zcash tokens to another person with a shielded address.

Part of the problem is that shielding is inconvenient. Mobile devices have no problems processing unshielded Zcash transaction but lack the bandwidth and power to allow for shielded ones. To get the benefits of shielding, a full node client must be set up on one’s desktop. But this is complicated to orchestrate. Third party wallets provide a simpler means for regular people to store and exchange Zcash tokens, but these wallets only allow transparent transactions.

Even when anonymity is simple, as in the case of cash, it isn’t a terribly popular feature. Make it less easy to enjoy anonymity, as in the case of bitcoin and Zcash, and it becomes even less desirable.

I’m sure that at some point, Zcash and bitcoin will overcome these technical hurdles and provide a friendlier experience with anonymity. But even then, there remains another type of inconvenience. Rules and regulations often impede the ability to make an anonymous payment.

For instance, one of the big problems with a shielded Zcash payment is the tax treatment. If you were paid some Zcash yesterday and spent it today, you are required to compute and pay income tax on any gains you may have accrued due to Zcash’s price fluctuations. With a credit card payment you may give up your anonymity, but at least it doesn’t trigger a burdensome taxable event whenever you use it.

Credit cards are another example of how rules prevent people from choosing financial privacy. I wrote earlier how rewards tempt people away from anonymous cash payments. Bank and card networks don’t provide customers with these perks for free. They recoup the cost through a toll levied on retailers, otherwise known as interchange.

Only three percent of respondents said that they owned bitcoin because it “allows me to make payments anonymously.”

By putting a surcharge on each card payment, retailers would be able to offset the interchange fees they must pay. From the perspective of a consumer, a surcharge on each card payment would nullify the benefits of rewards, thus putting cash in a more advantageous position. But Visa and MasterCard rules have traditionally prevented surcharging. The no-surcharge rule puts cash, and the anonymity it provides, at a big disadvantage.

Regulations also inhibit the usefulness of another type of anonymous payment instrument, prepaid debit cards. People can buy prepaid debit cards without having to provide any type of identification. But thanks to a constant stream of anti-money laundering regulations, the amount of prepaid value that people are capable of purchasing without revealing themselves is tiny (and getting smaller).

In Europe, new rules will reduce the amount of preloaded value that can be issued anonymously from 250 euros to 150 euros. These cards can be used online, but online payments will now be limited to 50 euros before the owner has to unveil themselves. With such as small window, prepaid anonymity just isn’t very useful.

If people are ever going to start using privacy-friendly payments options, then product designers will have to ensure that privacy is seamlessly integrated into the payments process. Making anonymity the default option would be a big step. But these technical fixes won’t be sufficient. Regulatory fences that privilege non-anonymous payments will have to be leveled, or at least holes will have to be drilled.

Even if regulations are loosened and technical problems solved, there is still the problem of apathy. Even though cash’s anonymity is easy to access and users face little in the way of regulatory hassle, survey results tend to show that people don’t value the privacy that a banknote provides. If technologists and privacy advocates are going to get us all to put more value on anonymity, they’ll have to keep on educating us about its value.