Nestled on an inlet of the Clatskanie River, an hour or so outside of Portland, Clatskanie is a small timber town, where the residents mostly spring from Nordic and Germanic stock. Its claim to fame, small but significant, is that Raymond Carver was born there.

Linda DePersis is the owner of Clatskanie Floral, a florist stocked from her own flower farm just outside of town. The store’s website shows DePersis wearing jeans and sturdy boots, standing in a lush field with a bunch of pale pink flowers under her arm above the caption, “Linda harvesting a bed of tulips.”

When DePersis looks at her website, she uses a super-fast internet connection—something that many in rural America can only dream of. At the front of her farm is a large antenna that beams data over the two or so miles to a computer repair shop in the town center. There, a central connection point caters to local mesh network users, measuring usage by the data packet and taking payment in cryptocurrency.

“We’re super excited to get this quick internet,” DePersis says in a phone call. “It’s so fast, we’re loving it.”

The computer store is run by Deborah Simpier, cofounder of a company called Althea. Althea promotes mesh networks by providing custom firmware to run on internet routers, and an experienced team to help with the process of getting new networks off the ground.

Here’s the concept: In everyday internet usage, the local network structure we most commonly encounter is a “star network,” where each end-user device (also known as a node) connects to a central hub which controls all of the functions of the network, like a home wifi router managing traffic from a laptop, smartphone, connected TV, and so on.

But this isn’t the only way a network can be organized. When set up correctly, multiple routers can connect directly to one another and cooperate to route data through the network efficiently in a mesh configuration. This network topology can be seen in many well-designed offices, where a main router is connected to the external wired internet connection, and shares this connection wirelessly with a number of satellite routers distributed through the space.

There’s no need for a subscription either, as payments are made directly in cryptocurrency.

Effectively, Althea extends this same principle to internet-sharing in communities that are badly served by existing ISPs, helping them to set up their own decentralized internet services (see a demo here). The aim is for community members to pool their resources and buy a commercial grade internet connection, then distribute the bandwidth over a local mesh, which works out at better value than if each had purchased an individual home broadband package.

Not only that, but there’s no need for a subscription either, as payments are made directly in cryptocurrency.

“The basic concept here is that our software allows routers to pay each other bandwidth,” says Jehan Tremback, another of Althea’s founders. “You can set up this equipment with long-range WiFi antennas, and it connects to other similarly enabled equipment and forms a network where you just put cryptocurrency into your router and get internet access, which you pay for as you use it.”

Althea’s software uses micropayments to incentivize and balance the flow of data around the rest of the network. Routers each have a wallet address that, like a pay-as-you-go phone, is pre-loaded with balance in the form of Ether, and makes a stream of small payments to any node that forwards their internet traffic towards the external connection.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

The Clatskanie mesh currently serves about 25 internet users with higher speeds than they can get from a fixed-line connection, and for a fraction of the cost. DePersis estimates that her Althea router costs about $20 of ETH per month, easily meeting her family’s internet needs. That compares to the more $100 she was paying previously for a broadband connection that often struggled to handle multiple downloads simultaneously.

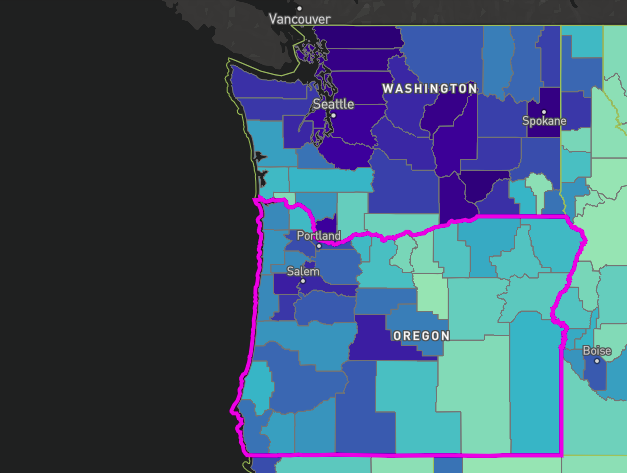

Poor internet speeds are typical for much of Oregon. The FCC publishes an interactive map of broadband deployment across the US which shows the number of local providers that can offer a connection in a certain speed range. The image below shows the map filtered for connections equal to or faster than 25 Mbps, the minimum download speed classed as broadband by the FCC since 2015. (As a benchmark, 25 Mbps is the minimum speed Netflix advises to stream videos in 4K resolution.)

A light green shade represents a single ISP able to deliver connections at a given speed, so in terms of geographical area, large swathes of rural Oregon exist in a monopoly market where only one provider can furnish the Netflix-minimum. By population, 67 percent of Oregonians are served by three or more providers at this tier of broadband, with another 25 percent having a choice between only two.

This urban-rural connectivity divide exists all across America. It’s been called the “homework gap,” because it prevents children in rural areas from completing homework assignments requiring online research, perpetuating urban-rural inequality. There are other consequences too: In a recent video clip, presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke said lagging internet speeds mean rural Americans can’t even “go to Tinder and find a date tonight, find that special person who can make a difference in their lives.”

Networked incentives

Rural America struggles with the digital divide because its population represents a comparatively small market segment, leaving telecoms companies reluctant to make investments in the infrastructure necessary to operate there. But collectivizing internet access might be a solution. In badly served areas, it can be more feasible to put in one commercial-level fiber connection than to get a moderately fast broadband package delivered to multiple homes.

“You might picture the internet backbone and think that must be where big corporations and the government really control things,” says Tremback, referring to the network of major fiber-optic cables that carry data across the U.S. like the interstate system for web traffic. “The reality is, it’s the last mile that’s really monopolistic,” he says. “Getting the connection to everybody’s house in town is actually a lot more work than digging a very small hole across the country to run a fiber connection into a datacenter.”

Under Althea’s model, the economics of the last mile distribution are shifted by socializing internet access. Any router with a connection to the global internet can act as a gateway node, sharing that connection with other nodes in the network and being paid for data forwarding in return. This means that if users in a given area can arrange for one high-speed, high-bandwidth connection, the community can take charge of how to distribute it among themselves, developing the kind of local network infrastructure that a traditional ISP might be reluctant to install in an area deemed unprofitable.

At the same time, the owner of any router running Althea’s software can decide to operate as an “intermediary node,” defining a price in cents per gigabyte for providing the forwarding service to nodes that are further away in the network.

The system is set up to ensure that users receive the fastest and best possible price for broadband. Althea’s algorithm automatically looks for optimal paths data should take through the network. It’s in the interest of gateway and intermediary node owners to sign up more users to the network, since more through traffic brings more forwarding payments; and in turn, as the number of nodes in the network grows, competition for that traffic brings down the fees.

No contract, no installation fees (besides buying an appropriate router), and no obligation to stick with the Althea network if a better option presents itself.

The result is a market for bandwidth which users participate in only on the basis of actual data consumption: No contract, no installation fees (besides buying an appropriate router), and no obligation to stick with the Althea network if a better option presents itself.

As Tremback and Deborah Simpier explain, besides the networking software itself, part of Althea’s innovation is in designing the right system of incentives for building and governing resilient networks. Before co-founding the company, both were involved in running mesh networks elsewhere, but saw problems with long-term sustainability in volunteer-driven projects.

“Mesh networks are often trying to be ‘free as in freedom’ as well as ‘free as in beer,’ so they don’t want to charge money,” Tremback says. “I was thinking about ways to keep the same decentralization but bring more money in to make it sustainable, and that’s how we came to [the idea for] this project, and to cryptocurrency.

Utility or mesh?

Given that rural America is under-served by traditional telecom models—24 percent of rural Americans describe broadband as a “major problem,” according to Pew Research—you might think that lawmakers and regulators would be supportive of alternatives. Unfortunately, legislators in many states, and the FCC—have often taken positions that hinder the development of municipal broadband networks, and enshrine the rights of existing telcos to be the only organizations that provide connections, critics charge. But the tide may be turning, as evidenced by the number of candidates—Beto included—who are embracing equal internet access as a campaign issue. Christine Hallquist, a gubernatorial candidate in Vermont, is campaigning on a proposal to make power utility companies install fiber-optic cables in their areas of service, putting universal broadband access on a par with the right to electricity; and Tennessee senator Janice Bowling has been repeatedly trying to pass a bill that will allow communities to improve connectivity for themselves.

The public utility model of internet services has already been highly successful in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where broadband provider EPB is owned by the city, and is now the most favorably rated provider in America according to a survey by Consumer Reports (it’s a low bar, but still). The idea of internet access as a right, like power and water, is starting to catch on, with hundreds of communities across the U.S. now setting up from some form of publicly owned network.

In light of that, Christopher Mitchell, director of the community broadband networks initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, expressed some doubt that the distributed, incentivized but non-comprehensive model used by Althea would be appropriate as a general template.

“I worry mainly about the likelihood of their approach being able to offer universal service in a given community,” he says. “We don’t see many efforts to self-organize to build roads and I’m not sure it is the best approach for digital infrastructure. That said, we believe in the importance of overlapping networks and hope this arrangement results in more networks. But our work is concerned with networks that will connect everyone and support the economy of an entire region.”

Althea’s trial network is currently small, but it’s a big idea in the making.

But, as Mitchell says, overlapping networks can co-exist, and there’s no reason that local mesh-nets should impede the development of more comprehensive municipal broadband projects. They may be a valuable intermediate step, something that can be deployed in an agile fashion while public projects get up and running.

Althea is a project that embodies the more public-spirited principles of libertarianism: a desire to reduce bureaucracy by furnishing the tools of self-reliance, and letting communities provide for themselves in a way that improves efficiency. It’s also an example of how cryptocurrency—which greases the real-time market for bandwidth—can enable a system that would be hard to run using traditional money. Althea’s trial network is currently small, but it’s a big idea in the making. Rural Americans stand to gain a lot from mesh networks—even if most of them don’t know it yet.