App developer John Watkinson had never signed a piece of art before. He certainly hadn’t signed one that would grace the walls of a gallery in Zurich, Switzerland—a country he’d never visited—alongside a piece by the famous Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. Until recently, he’d never introduced himself as an “artist.”

“I’m nervous about signing these,” Watkinson said one day in October in his shared office space on Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, bent over a printed image of a CryptoPunk—a simple, pixelated image of a man with a beard, mohawk, and sunset-colored glasses. “I’m one of those computer guys who never learned to handwrite anything.”

Watkinson practiced his signature a couple times before marking the 12 CryptoPunk prints that would appear in the “Perfect & Priceless: Value Systems on the Blockchain” exhibition in November at the Kate Vass Galerie in Zurich. He’d been invited to exhibit his work there by Georg Bak, a Swiss curator and digital art expert, while appearing at a blockchain conference at Christie’s, the famous auction house, in London—another thing the computer programmer never expected to do.

“And here I go,” Watkinson singsonged as he signed the first Punk. An illustrator, Jen, who works in Watkinson’s office space, helped Watkinson photograph the Punks and decide which pencil he should use to sign. She’s a professional artist, as are a few others who use the workspace, so they helped Watkinson prep the technical details for the show. Do you write “1/1” on each, one-of-a-kind print? Yes—Watkinson didn’t plan on printing any additional copies. Like the Punks themselves, the corresponding prints would be unique.

In the art world, ensuring that a work is unique, hasn’t been tampered with, and was created by the artist an auction house says it was are the key aspects of determining its value. That’s why the notion of provenance, or the record of ownership, is central to this industry, where forgeries are so prevalent the U.S. president reportedly has one.

The CryptoPunks address all of these key value aspects. Thanks to blockchain, each Punk is certifiably unique, you can’t mess with its appearance, and you can track exactly who’s sold or purchased it and for how much money—all without the need for an auction-house intermediary, agent, or gallery. In this way, blockchain could be a threat to the art-industry establishment. In another version of events, auction houses could use private blockchains to track provenance, removing easy-to-lose (or forge) paper records and unifying the entire, international body of famous art in a single, digital system.

The Punks successfully address these value aspects because they’re purely digital. Attaching a physical piece to a digital ledger remains complicated (it takes a certain amount of trust to sell your blockchain-tracked Picasso to someone else and assume they’ll go on to digitally record what they do with it). So each CryptoPunk print comes with a wax-sealed envelope, rubber stamped with the image of a Punk, featuring a QR code that links to the corresponding Punk’s description page. Inside the envelope, a “paper wallet” (aka, a mnemonic code) confers ownership of a unique, Ethereum-based token—what makes each Punk certifiably one-of-a-kind, and what makes them such groundbreaking art. It still takes good faith to assume the owners will keep the prints with the envelopes and their contents, but it’s the ownership of the digital piece that’s most valuable, anyway. That will endure even if the print or the physical certificate goes missing down the line.

CryptoPunk print with envelope and QR code. Photo by author.

“This might be my favorite,” Jen said, pointing to a Punk with a purple hat and lipstick. She gestured to another. “I like this guy because he reminds me of a friend of mine.” This was the first time Watkinson was seeing the physical form of the “art pieces” he created using a digital character generator he designed nearly two years ago, a casual experiment he worked on with his partner and only colleague at Larva Labs, Matt Hall. The pair, both Canadians who met while attending college in Toronto, started Larva Labs to make mobile apps for the T-Mobile Sidekick. They’ve since gone on to write apps for iOS and Android and work for clients including Google and Microsoft. While Watkinson was signing the first prints, Hall was in Japan giving a talk on both the CryptoPunks’ nonfungible tokens (NFTs), and the pair’s new music business, Choon, which Hall said is “basically SoundCloud but with a token.”

“For a while, we described ourselves as programmers, developers, or engineers,” says their website, “but it seems these days the best term is ‘creative technologist.’” The CryptoPunks have made them not only artists, but also pioneers in the growing world of “blockchain art,” inspiring the lowbrow CryptoKitties and paving the way for high-concept pieces by the likes of video artist Eve Sussman, whose past works have appeared at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery in London. If cryptocollectibles ever truly become mainstream, it started with Watkinson and Hall.

Watkinson signed a Punk with a shock of red hair smoking a cigarette. It’s one of his favorites in print form. When I asked whether he thought he’d ever be spending this much time with the CryptoPunks, Watkinson immediately answered, “No.”

CryptoPunks started with a pixel-art character generator Watkinson began playing with in December 2016. It randomly mixed a selection of characteristics (sunglasses, skin colors, hair types, and so on) to come up with 10,000 24-by-24-pixel “punks”—a characterization that nods to the early ‘90s cypherpunks, cofounded by the late Timothy May. None look exactly alike, and certain types of punks turned out to be rarer than others. There are only nine “alien” punks, for example, while most resemble humans, some look like zombies, and a few look like apes. “We were not quite sure what to do with them,” said Hall. “We thought maybe we would make a game out of it. Or like, an app with some collectible aspect to it.”

They’d been thinking about incorporating bitcoin into one of their projects, but then they started looking into Ethereum. There were no nonfungible (aka, not interchangeable) Ethereum tokens at the time. The point of tokens so far was to be fungible, so the ERC-20 tokens could work like currency, where any one dollar bill is exactly equivalent to any other. There was no need for a token to be totally unique. Not until you applied it to something rare, collectible, and one-of-a-kind, like the Punks.

“We muddled our way through figuring out how an ERC-20 token would look if it were not fungible,” said Hall. After many attempts, they settled on putting the hash of each CryptoPunk’s image file into its respective smart contract, including some “marketplace functions” that would allow people to buy and sell the Punks. They posted their project to the Ethereum subreddit and Hacker News and waited for people to notice. Very few did. About 100 claimed a Punk, which Hall and Watkinson offered for free.

Then, in June 2017, the pair got in touch with Mashable and told them about CryptoPunks. “This Ethereum-based project could change how we think about digital art,” read the headline above an image of a blond, glasses-wearing Punk with the caption, “Someone owns this picture.”

“Things went crazy,” said Hall. “We went from having something like 8,600 [CryptoPunks] available to within 20 hours, they were all claimed.” The pair had already reserved 1,000 for themselves “just in case it becomes a thing.”

Watkinson got in on the action. The day the Punks exploded, he sold one of his for a dollar. Someone bought it, so he sold another for $10. That sold, too, so he went up to $50, then $100. That same day, someone offered an alien Punk for 10 ether, which at the time was $3,000. “Boom, someone bought that,” said Watkinson. “I was just like, whoaaa. The day before that, we were like, will anyone care?”

When CryptoKitties, by far the best-known cryptocollectible, debuted in November 2017—as the price of ether climbed steadily upwards of $400—they were so immediately popular that people trading them slowed down all transactions on the Ethereum network. These either adorable or disturbing-looking digital cats (depending on who you ask) wouldn’t have existed without the CryptoPunks.

Mack Flavelle, the Vancouver-based founder of CryptoKitties, ardently opposed Napster when it came out in the late ’90s. The fact that it provided a way for anyone on the internet to share music peer-to-peer without paying artists or record labels bothered him. “We live in this super-weird blip in the history of the human species where until recently, ownership meant if I had it, you couldn’t, because things were tangible,” he told me in December 2017. He was “inspired by CryptoPunks,” he said, to come up with a blockchain-based token that would “reflect the true nature of ownership.” That became the NFT, ERC-721.

The ERC-721 white paper explicitly refers to the Punks: “There are many proposed uses of Ethereum smart contracts that depend on tracking distinguishable assets. Examples of existing or planned NFTs are LAND in Decentraland, the eponymous punks in CryptoPunks, and in-game items using systems like DMarket or EnjinCoin.” The paper also mentions Rare Pepes, another collectible, digital crypto-asset that preceded even the Punks (they are not alt-right memes but rather a more innocent appropriation of Matt Furie’s green frog). However, as the ERC-721 white paper points out, they are “not distinguishable assets,” but rather a “collection of individual fungible tokens, each of which is tracked by its own smart contract with its own total supply.” For the rarest Pepes, that supply is just one.

The creators of all these different cryptocollectibles came together for the first time at the Rare Digital Art Festival, which took place in New York in January 2018 and drew around 300 people. During one panel, a cardboard cutout of “DJ Pepe,” with DJ J Scrilla providing the voice Wizard of Oz-style from the back of the room, spoke alongside Flavelle, Hall, and the creators of DADA, a collaborative, digital art market that today thanks Watkinson on its website for his “generous advice and support.”

After a day of talk about democratizing art and defacing one-dollar bills in exchange for promised tokens, the festival’s organizers put on a live auction, the first of its kind for blockchain art. A rare Homer Simpson pepe sold for the equivalent of $38,500 to the good-humored heckling of a beanie-wearing crowd. The buyer was a marketer who’d flown in from Florida to attend the event—he didn’t even have a Pepe Wallet in which to store his new purchase.

“People say this was the seminal crypto art event,” said attendee Jason Bailey, editor and creator of the art tech blog Artnome. Before, everyone in this space had been working on their projects disparately. Some knew of each other, others didn’t, but this was “the first time they all realized that each other existed, and maybe this was more than just random mavericks playing with tech in ways no one else had yet.”

Like Hall and Watkinson, Bailey stumbled into blockchain art significance by accident. Late December 2017, when cryptocurrency prices were spiking, he wrote a blog post on Artnome called “The Blockchain Art Market Is Here.” Because of the high search traffic for “blockchain” at the time, Bailey’s post ended up being the top story on blockchain art, bringing him into the fold of this niche community.

Everyone I spoke to who’s involved in blockchain art either has a CryptoPunk or wants one. Many of them picked out Punks that resemble someone—themselves, their family, or celebrities.

![]() One of Bailey’s Punks, for instance, “kind of looks like me,” he said, “if I had a gold earring and a durag on.” He uses it as his Twitter avatar. Another CryptoPunk owner I spoke to (who didn’t want to be named) bought three shortly after the Mashable article published—two that looked like his daughters, and one that reminded him of his wife.

One of Bailey’s Punks, for instance, “kind of looks like me,” he said, “if I had a gold earring and a durag on.” He uses it as his Twitter avatar. Another CryptoPunk owner I spoke to (who didn’t want to be named) bought three shortly after the Mashable article published—two that looked like his daughters, and one that reminded him of his wife.

Andrey Alekhin, the CEO of Snark.art, a new blockchain art effort that’s so far produced a tokenized video art project by Sussman, bought ether in January 2018 “mostly to buy CryptoPunks,” he said. “Of course, I wanted to buy the zombies, but they were quite expensive at the time.” He owns three, now, and his strategy is to collect Punks that resemble celebrities because that might make them more valuable in the long run. So far, only one of his three looks like somebody remotely famous—the German artist Joseph Beuys.

Alekhin isn’t alone in his thinking. There’s a website dedicated to matching CryptoPunks with their celebrity lookalikes. You can find pretty decent matches for Hulk Hogan, John Waters, and, if you’re being generous, Katy Perry in her blue hair days.

Others just buy Punks that they find visually pleasing, like Alekhin’s Snark.art cofounder, Misha Libman, who has a couple. Sussman has yet to buy one, she told me, “but I will.” Kevin Abosch, an established multimedia artist who’s done innovative work related to blockchain—including stamping out Ethereum contract addresses with his own blood—bought three CryptoPunks after hanging out with Hall and Watkinson. “I got one with VR glasses, one with red hair—simple ones,” he told me. (The Zurich show’s title, “Perfect & Priceless,” comes from something Abosch said about his project with Ai Weiwei, in which the pair tokenized their “priceless” moments together. Their piece, “Priceless,” headlined the show.)

“I know there were people who say that CryptoKitties are works of art,” said Abosch. “They don’t excite me so much. CryptoPunks, on the other hand, do. I don’t know why. I do, I really like it.”

Hall and Watkinson themselves make a similar impression. People just like them. Besides their trademark Canadian kindness, they’re also humble for a pair being asked to speak internationally at esteemed art establishments and educational institutions. “I think it was easy for me to assume up front that Matt was sort of the face of the group…and John was more the programmer,” said Bailey. “The more I got to know them, the more I realized that wasn’t true. John is a great presenter, and Matt knows his stuff from the tech side. That’s what makes them such a powerful duo—they’re complementary but both more than capable.”

CryptoPunks have moved slowly from the blockchain art world into the establishment one. In May 2018, a CryptoPunk sold for $950 during an art auction at the Brooklyn Ethereal Summit alongside an $8,500 Abosch. Then in July, Hall spoke on a panel at Christie’s in London during a conference titled “Exploring Blockchain.” While most of the panels droned on about General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the importance of provenance, the digital art panel—moderated by Bailey and featuring DADA’s Judy Tam—was lively, making it “one of the more popular panels of the day,” Bailey said. None of them ever imagined they’d be on stage at Christie’s, so they had fun with it, unpretentiously discussing a topic they really cared about (compared to those who had to speak about a technology that could threaten auction houses’ esteemed positions as the go-between in pricey art sales).

Watkinson sat in the audience during the panel, so Hall pointed him out: “There’s the artist who made the CryptoPunks.” Bak was also in the audience. After the panel, he approached Watkinson about including the Punks in a show he’d been planning in Zurich.

Bak grew up in Zug, Switzerland, also known these days as Crypto Valley for its cryptocurrency-friendly tax laws. That’s how he got interested in the technology and its connection to the art world. Before that, Bak’s art interests lay mainly in things like the “generative photography” Gottfried Jäger pioneered in the 1960s. Being both generative (meaning it was designed by an autonomous system—Watkinson’s pixel character generator) and blockchain-based, the CryptoPunks intrigued Bak. In London, he and Watkinson discussed what they could put on display for a show—CryptoPunks being purely digital—and ultimately came up with prints and the separate, sealed envelopes featuring corresponding QR codes and containing paper wallets.

“That was a strange process,” said Watkinson. He and Hall turned to some artist friends, like the designers in their shared office space and a painter they knew, to counsel them on getting the best materials for bringing the Punks into the physical world.

“I was telling the gallery owner that we want to make sure that [the envelopes with the paper wallets] are considered what you’re buying,” said Watkinson. “That is the art, and we have the print and the print should look nice…but it should sort of be secondary. It should be pushing that it’s a digital good.”

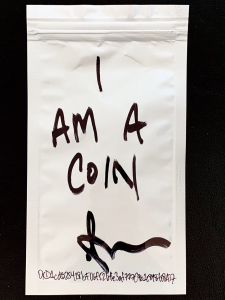

The day before the “Perfect & Priceless” opening on November 16, Watkinson visited the gallery to check in (Hall had stayed behind in New York). Unaccustomed to showing digital art, the gallery staff bumbled their way through wiring ethernet ports for mining equipment, and Watkinson paced the modestly sized gallery, walking past his CryptoPunk prints, framed flowers corresponding to ERC-721 tokens, and a Mylar foil pouch full of the extra blood Abosch drew for his IAMACOIN project. Bak had already stopped promoting the show, because so many had RSVPed to the opening.

Earlier that week, Watkinson and Bak gave a talk in Zug about the CryptoPunks during an upscale dinner that would kick off a blockchain finance conference. The attendees included Niklas Nikolajsen, founder and co-CEO of Bitcoin Suisse, and someone Watkinson described as “Crypto Valley’s Joe Lubin.” (Lubin being a founder of ConsenSys.) The aim was to drum up interest in “Perfect & Priceless,” but, said Watkinson, “it wasn’t really a CryptoPunks crowd.” They were wealthy, Swiss banker-looking types—ideal potential art buyers, but not the earnest nerds who would marvel at blockchain’s potential to 10x art for art’s sake.

However, the talk appeared to be well received. A bunch of the attendees, Bak told Watkinson, including a few “bitcoin billionaires,” would be coming to the show’s opening.

On opening night, the Kate Vass Galerie was packed shoulder to shoulder with digital art fans, tech nerds, longtime art collectors, and wealthy businesspeople from Zug. The description of the show made sure to allude to famous artists, likening a smart-contract piece by Ed Fornieles Studio to certificates Marcel Duchamp created in the 1920s and comparing visualizations of cryptocurrency transactions to “spot paintings” by Damien Hirst. An old-timey calculator sat on a pedestal, mining bitcoin impossibly inefficiently while printing an endless paper scroll of its operations—a piece called Bittercoin by César Escudero Andaluz and Martin Nadal. A crumpled printout of the blockchain contract address for a fraction of one of Abosch and Ai’s priceless moment tokens hung on the wall. It’s virtually impossible to crumple two pieces of paper the exact same way, ensuring in a physical manner the print’s uniqueness. Nearby, Abosch’s signed bag of blood sat in a wooden frame.

Watkinson and his girlfriend, a Google contractor named Gina Binetti, arrived at the opening half an hour after it started. Someone from the gallery approached Watkinson immediately to deliver the news: “You’re sold out.”

The gallery displayed nine framed CryptoPunk prints, and someone had bought them all. Three additional Punks and their prints, not on display, sold to three other individuals. They were the first works of the “Perfect & Priceless” show to sell.

CryptoPunks set of nine at the Kate Vass Galerie in Zurich. Photo courtesy of Georg Bak.

The art world is typically cagey about buyers, but Bak disclosed that the man who’d purchased the nine Punks was a younger collector of mainly contemporary art who’d bought from Bak before. He’d reserved the set before the opening even began. At least one of the other buyers had been at the dinner in Zug, while another came from the art world. “I didn’t know that there would be such a huge demand,” Bak said. A waitlist for buying additional Punks developed, and others—arguably the savvier ones—went online to buy Punks during the show. They got theirs for much cheaper than the 5,000 Swiss francs ($5,068 U.S.) people spent on each Punk with a print. The set of nine went for 35,000 francs, or $35,479. The CryptoPunks Ethereum contract has now processed over 20,000 transactions (you can see them here—transactions represent not only sales but also actions like placing bids).

A tan, bald man wearing an expensive watch approached Watkinson excitedly during the opening. He was a “kind of generic-looking guy,” described Binetti, but he felt he’d found his perfect CryptoPunk match, which he’d purchased online before the exhibition. “I wanted myself, and I found myself,” he told Watkinson, displaying his Punk proudly on his cellphone.

“Did it look like him?” I asked. Binetti said it did.

Two attendees, Hansjoerg Hettich, the executive director at Multichain Asset Managers Association, and his colleague, John Orthwein, had been following the Punks since the Mashable article. “It’s a new genre…the great art piece was not the picture on the wall but the one on the blockchain,” said Hettich. Both were so excited to meet Watkinson at the opening that they invited him and Binetti to dinner at Orthwein’s chalet in the mountains, where they could discuss the Punks at length over fondue. (November is fondue season in Switzerland.)

Orthwein’s modern chalet stands at the top of a steep, switchbacked hill by a lake an hour away from Zurich. While Watkinson, who doesn’t like cheese, snacked on mostly bread, the conversation kept coming back to the Punks. “We just covered all the bases,” said Orthwein. “Why this might be a new genre, how it might be perceived, this whole really elusive idea of digital scarcity and authenticity—it’s such a weird concept to wrap your head around.” They also talked about the possibility of creating more Punks.

“From a business perspective, you could imagine what you could do with the next 10,000 Punks,” said Hettich. “Maybe CryptoPunks with Donald Trump, with celebrities—that would sell…but then it would be too commercial. It wouldn’t be art anymore.”

But the Punks weren’t initially art. They were an experiment created by mobile app developers that accidentally lead to the creation of the NFT. Then they were more or less perceived as the original cryptocollectible—up until the Rare Digital Art Festival, at which point they became part of the “blockchain art” canon. No one was proposing they appear in a typical art gallery, not until people familiar with the history of digital art, like Bailey and Bak, began to recognize the Punks for qualities other than their unique, collectible nature.

Now, people consider CryptoPunks to be the first peer-to-peer art market. Even Christie’s—which held its first blockchain-registered auction the same month as the “Perfect & Priceless” opening—has recognized the Punks’ importance by inviting them to talk about provenance and sales history. It’s been over a year since the Punks got popular (a relative term when we’re talking blockchain art), and some have a robust history of sales and bids encoded into their identity. “It’s cool how that record will never go away,” said Watkinson. “It will always have this perfect memory of exactly what happened.”

About a week before “Perfect & Priceless,” Bak quietly curated another digital art show at a private residence in Paris. He invited Watkinson and Hall to display artwork.

The pair submitted a printout of a QR code that, described Watkinson, “when scanned by a phone’s camera, generated a little pixel artwork that the user could save.” Everyone who went to the show, then, could walk away with their own small piece of digital art.

Hall and Watkinson are still working on making a “pure blockchain version” of the piece, where the generation of the art happens entirely on the blockchain, “with no external code or servers required,” Watkinson wrote to me in an email in January. “We’ll see if we can make it work!”

According to Bailey, artists are always forging ahead and creating new work. “Business people stumble onto one thing once and run it into the ground, seeing how much they can get out of it. Blockchain people become almost religious about using blockchain. Artists—the thing they become known for is just one thing,” said Bailey. “There’s no doubt to me that John [and Matt] are artists.”

The Punks remain a source of income for Larva Labs. The pair recently printed 12 additional Punks to send the people on the waitlist from the Zurich show (about which Watkinson will surely feel more comfortable signing). Then it’s time to take a break from the Punks for a while. Hall and Watkinson have other projects they’re working on, like their blockchain music startup, and they recently bought a “new toy” to experiment with, a plotter—essentially, a printer that can take instructions from a computer to draw images IRL.

The plan so far is to use the sort of generative, blockchain-based process that created the Punks, but to adapt it to the physical world using the plotter. Much more than the prints of the CryptoPunks, this process closely ties a digital work to a physical piece. If someone were, someday in the future, to buy a physical art piece created using the plotter, no one would need to insist that what they’re purchasing is a digital good. It inherently would be.

This story has been updated to reflect that the envelopes sold with the CryptoPunk prints included paper wallets, not just QR codes.