Over the weekend, an EOS “community updates” Telegram group reported the transfer of 2.09 million EOS (worth $7.26 million at time of writing) by a blacklisted account. Many reported this instance as the work of a “hacker,” but that’s not quite what took place. What happened really is about the breakdown of an early EOS arbitration group’s bandaid solution for blocking nefarious accounts. Confused by that word salad? To really understand, we first have to break down how EOS works.

Okay, so how does EOS work?

EOS is a decentralized operating system that supports dapps (like Karma, essentially Instragram with token incentives that’s available on iOS and Android). It’s different from other blockchains because instead of proof-of-work, it operates via a delegated proof-of-stake system, or DPoS. The EOS system is able to run faster than PoW or other PoS systems because there are only 21 main EOS nodes, or block producers, that have to validate transactions—as opposed to the numerous distributed miners in other blockchain networks.

Everyone in the EOS network votes on the top 21 block producers, and the tally of these votes happens every 60 seconds.

Related: EOS Arbitrator Intervention Raises More Questions From Critics

Technically, the top 21 block producers could be different every minute, and they do change fairly frequently. “The job security of a block producer is 60 seconds long,” says Kevin Rose, the cofounder and head of community at block producer EOS New York. EOS New York has been a top 21 block producer since it was founded, but that’s not by accident. Its members work constantly, and they’re based all over the world to ensure 24/7 operation. When U.S.-based members of the block producer are asleep, for example, Chinese members can continue working. Rose personally says he works “from the moment I wake up to the moment I go to sleep nearly every day.”

That’s a lot of dedication. How is someone like Rose rewarded?

By getting paid for the production of new blocks. Block rewards in the network are always one percent of the total EOS token supply, and are paid out across all EOS nodes that get an adequate number of votes, whether or not they’re among the top 21. Of that one percent, three-fourths goes toward “voter pay,” which is distributed across all nodes based on an algorithm determined by community votes. The other quarter goes to “block pay” and is alloca

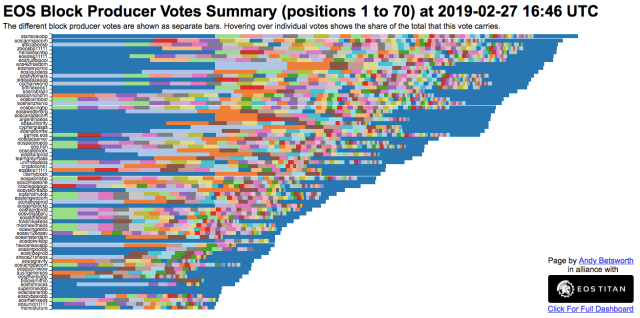

If you’d like a headache-inducing visual of the top 70 block producers, try making sense of this. Image found here.

ted across the top 21 block producers. Votes determine how much of the pot each block producer gets.

These votes are clearly important. What determines how EOS community members cast their votes?

“Any token holder is able to vote for any registered account as a block producer, for any reason at any time without permission,” says Rose. It’s like voting for a politician, he elaborates. You can vote based on who think is doing a good job, whether their views of how EOS should operate align with yours, or your mood that day (or rather, your mood that minute, in EOS voting tally time).

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

This is why communication is essential to keeping a block producer in the top 21. For English speaking participants, Telegram, Twitter, and direct emails are some of the big ways block producers communicate with voters. Other times, it’s appearing on “talk shows or podcasts,” says Rose, like politicians, or traveling to other countries where EOS tokens are concentrated, like China and South Korea. “It’s a global job,” he says.

What about the “hacker” who stole 2.09 million EOS? That’s why we clicked on this article, damn it.

The answer to that questions starts with ECAF, or the EOS Community Arbitration Forum. ECAF was not elected, like the block producers, but rather defined in the EOS Constitution, says Luke Stokes, a Puerto Rico-based member of the eosDAC community, another block producer. ECAF was meant to resolve disputes in the community. For example, if someone said another account stole their tokens, ECAF (after determining whether this claim had merit) would issue an order putting the guilty account on a blacklist.

To ensure this blacklist is upheld, the top 21 block producers must have that blacklist configured into their nodes correctly. This makes it so when those blacklisted accounts try to execute transactions, the transactions get frozen immediately, so the tokens from that transaction don’t wind up with a bad actor.

However, the more blacklist orders ECAF submitted, the more block producers grew frustrated, pointing out that a growing blacklist to ensure EOS security wasn’t “scalable,” says Stokes. They started proposing alternative security mechanisms for guarding tokens, like multi-signature and time-delayed permissions. Plus, since the top 21 block producers had to agree on which accounts to blacklist, it felt kind of like censorship, which didn’t appeal to EOS’s otherwise permissionless ethos, he says.

So what about those stolen 2.09 million EOS already?

The blacklist, says Stokes, “creates these really incredible expectations in the community that [it] can somehow protect people’s property.” In reality, one top 21 block producer failing to correctly configure the blacklist would make the entire network vulnerable to bad accounts. And that’s exactly what happened with the 2.09 million EOS.

A new top 21 block producer, games.eos, didn’t correctly set up the blacklist. So previously frozen 2.09 million EOS got transferred from a blacklisted account. The account immediately spread those funds all over the place, too quickly for EOS block producers to plug the leak. “I can tell you they’re no longer a block producer,” says Rose.

A key takeaway here is that this isn’t a “hack,” per se—and it didn’t happen over the weekend. The transfer that resulted in the moving 2.09 million EOS happened a long time ago. From Stokes’s perspective, the real problem is that the blacklist was a temporary fix, a bandaid covering the larger problem of preventing theft from bad-acting accounts.

What’s to prevent this from happening again?

The EOS community is working on it, but the top 21 block producers need to agree on a path forward. Besides the use of other security mechanisms like multi-sig and time-delayed permissions, there’s a current proposal to “null out the keys on the blacklist,” says Stokes—in other words, to replace the keys of the accounts on the blacklist so those accounts can no longer operate in EOS at all. Stokes believes that just two of the top 21 block producers so far have approved that proposal.

“The expectations that were set [by ECAF’s blacklist] never could have been met,” says Stokes. “We all knew this was going to happen.”

This article has been updated to reflect that eosDAC is not currently a top 21 block producer (though that could change at any time.)