On November 5, the distributed lending app RCN announced that it would begin administering peer-to-peer smart contract loans for the purchase of real-estate plots in Decentraland, the blockchain-based virtual world. Decentraland is an extremely promising project, and RCN’s loans are conceptually fascinating.

And yet, for anyone attuned to financial history, the idea of blockchain loans for virtual real estate is pure nightmare fuel.

Many people now creating the blockchain universe were too young to get the full experience of the 2008 financial crisis, so allow me to share my own tale. When the crisis struck, I was in the final year of a PhD program, and through a chain of collapsing leverage that led right to the Iowa state budget, my teaching assistantship disappeared. I wound up cooking omelets in a greasy spoon and taking tickets at a parking garage, at age 30, while I finished my dissertation and frantically searched for a post-grad job.

It was, in short, NOT GOOD. And at the heart of it all, as we would learn over the subsequent weeks, months, and years, were real estate loans, based mostly on fiction and stacked into wobbly towers disguised as an impregnable fortress of Good Money.

It was, in short, NOT GOOD. And at the heart of it all, as we would learn over the subsequent weeks, months, and years, were real estate loans, based mostly on fiction and stacked into wobbly towers disguised as an impregnable fortress of Good Money.

Here’s the thumbnail version: For about a decade before the crisis, banks were handing out mortgages to anyone with a pulse. As memorialized in The Big Short, Miami pole-dancers were floating four or five houses as speculative investments. That was in part because loan terms were deceptive, but mostly because of something called a mortgage-backed security, which allowed Wall Street to put a bunch of shitty loans in a blender, then sell the resulting shit-frappe as a delicious, top-shelf investment (with some help from corrupt rating agencies and a real estate bubble).

RCN’s Decentraland loans evoke the conditions leading up to the financial crisis because they’re layering risk on top of risk in a way that could obscure what’s really going on.

Inevitably, the underlying loans went bad. And then the securities went bad, and then I went from teaching at one of the top public universities in the U.S. to flipping pancakes for a few months. A lot of people suffered much, much worse. The resulting distrust of the traditional financial sector was what drove nearly everyone in crypto for the first half-decade, including Satoshi Nakamoto themself, who embedded a headline about a bank bailout in the genesis block of bitcoin.

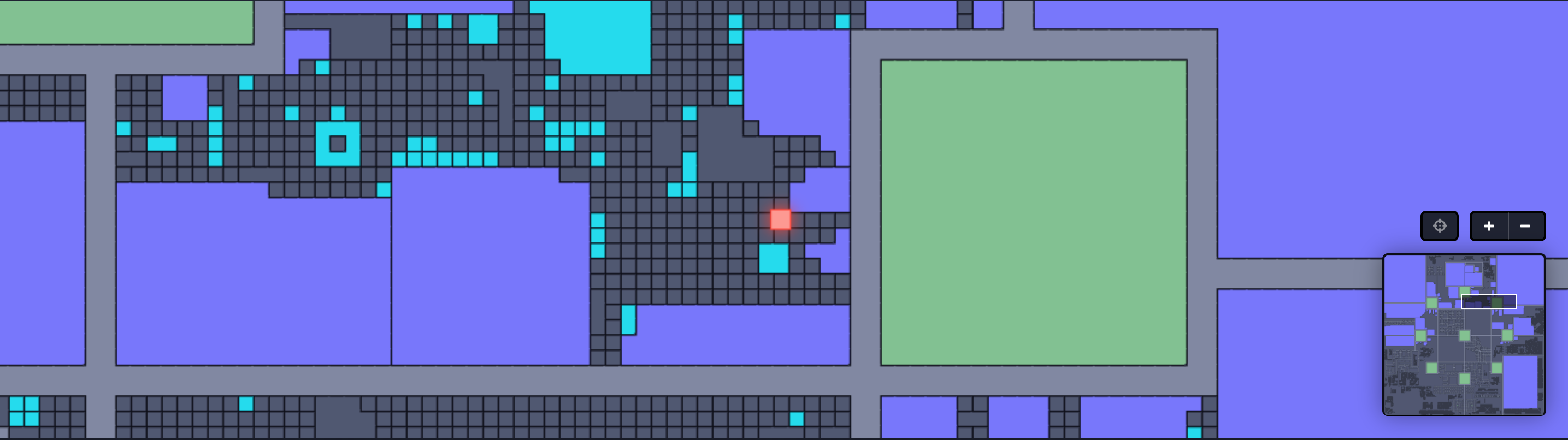

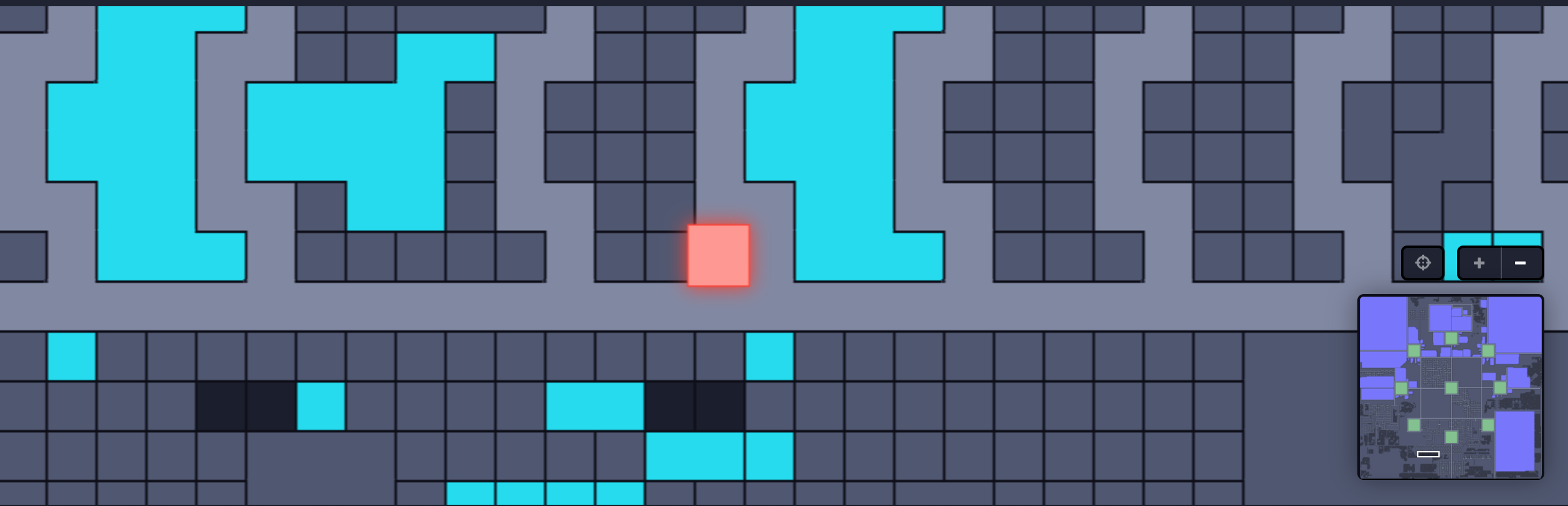

RCN’s Decentraland loans evoke the conditions leading up to the financial crisis because they’re layering risk on top of risk in a way that could obscure what’s really going on. To be clear, Decentraland is a very cool project, and buying parcels of their virtual land could be perfectly reasonable. Even without the true ownership promised by building virtual worlds on the blockchain, games like Second Life and Entropia Universe have shown that virtual real estate can have serious real-world value.

And the specific structure of the loans offered by RCN means they’re unlikely to directly create systemic risk. Though they’re called “mortgages,” the loans being requested on the platform right now are actually short-term—just three or four months.

That makes them, even in a hypothetical crypto-future, less attractive for the sort of securitization that can make a shaky long-term loan seem like a good part of your retirement portfolio. Further, these are person-to-person loans, which you could argue makes them more faithful to crypto’s individualist ethos.

RCN’s loans also leverage a safeguard that’s unique to crypto. They’re built as Ethereum smart contracts that link directly to the land parcel being funded, meaning that if a borrower defaults, they automatically lose access to their virtual land. (It’s unclear, based on RCN’s announcement, whether a lender would get to seize that land, the way a bank would.)

But the default scenario is what makes this scary in an entirely new way. Much as bad loans through the early 2000s were based on fiction—falsified income statements, mass delusions about forever-rising real estate prices—the underlying assets being financed by these crypto-loans are not real, in several senses. Decentraland is, of course, virtual, so even with the addition of blockchain, parcels aren’t as guaranteed to retain value as real land or houses.

That’s especially true because Decentraland is still getting off the ground, so there’s no airtight guarantee that buyers will ever be able to actually use the virtual land they’re borrowing to buy. If Decentraland collapses, either as a project or just as something people think has financial value, loans made through RCN will go belly-up. Even if they’re not held by banks and disguised as risk-free AAA assets, the unwinding of a bunch of crypto loans could have broader impacts.

I’ll admit, that’s a reach. This is a very small-scale offering so far, with only two loans being requested via RCN at this writing. And the amounts, while surprisingly large for speculative virtual assets, aren’t that big in broader terms; a parcel of Decentraland will set you back the equivalent of between $1,000 and $2,000 in old-fashioned money.

Related: We Haven’t Learned from the Financial Crisis—Just Look at Crypto

Nonetheless, my knees quake when I contemplate the future this small thing might portend, because it’s part of a broader romance unfolding between crypto and Wall Street. Some elements of that seem fairly innocuous—for instance, “security tokens” would simply use blockchain to make trading traditional stocks and bonds more efficient. But other things, such as the push for a bitcoin-based exchange-traded fund (ETF), could open the door to major banks and other institutions building complex financial products on the back of what is still a pretty risky asset.

That should give everyone in the blockchain world at least a moment of pause. Taking our financial fate back from big banks and professional investors shilling complex, risky investments was the entire point of bitcoin. Decentraland and RCN are conducting an interesting experiment, but extreme care needs to be taken with anything with even a whiff of systemic risk.

Because I really don’t want to go back to frying eggs for a living.