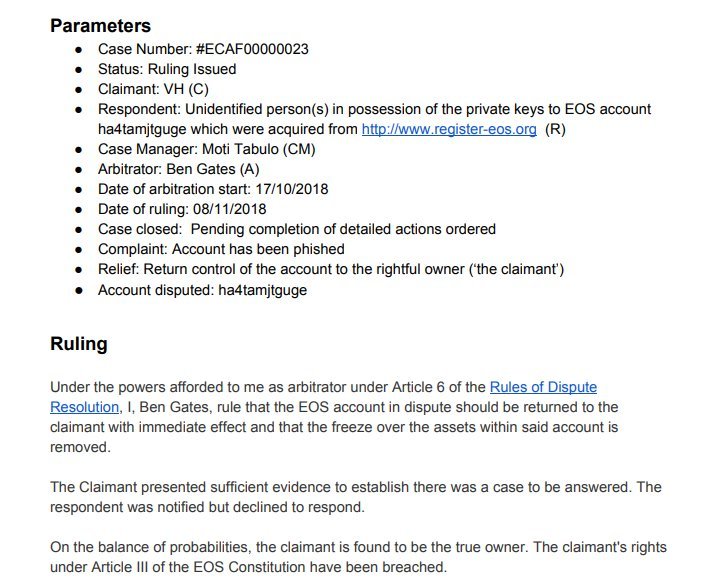

On November 10, Reddit user auti9003 submitted a post to the /r/Cryptocurrency subreddit with the title, EOS centralisation in action: arbitrator rules to reverse transactions from accounts. The post included a screenshot from a ruling posted in ECAF, the EOSIO Core Arbitration Forum, in which control of a hacked account was returned to the original owner.

Response to the post from other Redditors was largely critical, with commenters ridiculing the mutability of the EOS blockchain, and the governance processes that allowed a single individual to make this kind of judgment call.

Taken on its own merit, the action described in the post was unremarkable. EOS founder Dan Larimer describes the protocol as a “governed blockchain,” and the dispute resolution mechanism is an integral part of this community governance structure. Through the ECAF forum, EOS holders can submit claims to a team of arbitrators chosen by the community, with details about all claims filed and their eventual resolutions posted on a public noticeboard.

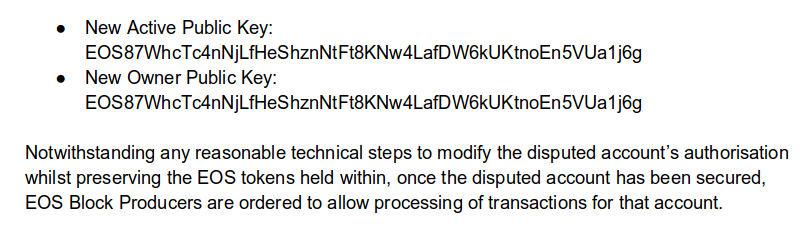

In the ruling on the claim in question, arbitrator Ben Gates notes that the claimant was able to prove prior ownership of the account in question, and no evidence was produced to dispute the claim that control over it had been obtained through a phishing scam. As a result of the ruling, EOS Block Producers were ordered to modify the public key corresponding to the disputed account.

Whether you think this is a legitimate course of action depends largely on what properties you consider as integral to a cryptocurrency. The ability to reinstate ownership of a hacked account by decree speaks to a degree of centralized governance that’s unheard of in the bitcoin network, for example.

But then, EOS doesn’t claim to be decentralized in the first place. And for users of digital payment systems like PayPal or Venmo, who are accustomed to the presence of a dispute arbitration mechanism, knowing that a hacked account can be recovered could be a reassuring security measure rather than a vulnerability.

Criticisms leveled on the grounds of scalability are harder to dismiss. If every claim requires a notification to be circulated, and a potentially lengthy investigation, it’s easy to imagine bad actors purposefully choking up the arbitration process with bogus claims—effectively a denial-of-service attack on the institutions rather than the blockchain itself.

It’s also fair to question why EOS is intent on duplicating so many aspects of traditional legal and financial systems in the first place, given that users of those systems have plenty of services to choose from already.

However, given its $4.6 billion dollar market cap, there are plenty of users and investors who don’t need to be convinced that EOS is working just fine as it is.