Economists have been reluctant to embrace crypto. A quick look at early publications on the Blockchain Research Network (a research database that I run) tells a tale familiar to any serious student. So far academics have mostly asked questions like “is bitcoin really money?” and, unsurprisingly, this reductive line of inquiry has failed to entice many actual economists.

In fact, economists have long ignored money. While the giants of the field—Smith, Marx, Polanyi, Keynes, Hayek, and others—discussed subject, it has since largely fallen out of the mainstream. This is because, according to contemporary economics, money is merely derivative of deeper economic realities, and therefore, not worthy of study.

When bitcoin first burst into existence in 2008, it aroused the suspicion of central bankers. They concluded that while bitcoin was interesting, it posed little real threat to state-issued money; the idea of innovating with state-issued digital currencies—a hot topic among central bankers today—was still some way off. As alternative blockchains emerged in 2014, some scholars saw crypto as an interesting prism for studying currency volatility, money supply, and regulation. More recently, and largely led by Vitalik Buterin, they have started talking about a full “crypto economics.”

"Across the top five economics journals there’s not a single mention of bitcoin, cryptocurrency, or blockchain in any published article."

But most mainstream economists haven’t blinked. Across the top five economics journals there’s not a single mention of bitcoin, cryptocurrency, or blockchain in any published article. Let that sink in. The journals that define the contemporary study of economics have not once—not ever—published the word “bitcoin,” despite a decade of technological development, billions in investment, and front page news coverage.

Related: New Book Reveals Crypto’s Radical Origins

Out on the fringe, however, there’s a small cadre of rebel economists trying to change the ivory tower’s perception of crypto. Gina Pieters—an economist at the University of Chicago and contributor to two Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance reports—is one of these rebels. According to Pieters, crypto isn’t just about crypto. It also holds the keys to innovative new methods for studying wider economic phenomena, like previously hidden examples of governments manipulating exchange rates. Her research on exchange rates takes advantage of the fine-grained market data available through bitcoin and correlates it to official and unofficial fiat exchange rates. It turns out that bitcoin market data can show when governments are manipulating exchange rates, even when the manipulation is done in secret.

I spoke with Pieters for BREAKERMAG, about why economics hasn’t embraced crypto and how her research is developing new tools that break the mold. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Economists are the obvious people to study cryptocurrencies and yet there is this a tendency for them to respond with indifference or even outright hostility. Paul Krugman comes to mind. Why do you think that is?

In the early days of crypto, there was a lot of “get rich quick” talk and talk about how this is going to potentially help the underground economy—for example, Silk Road. The ICO boom also didn’t help this impression. There was a very strong feeling that crypto is more of a scam than anything fundamentally interesting.

What do you say to those who think there’s no intellectual value here?

Coming at the problem as an international economist, it’s interesting to see the difference between an American-based perception of the shortcomings or the lack of value and what you see from an international economy perspective. If you’re thinking of it as something that’s going to replace the credit card system or the bank system in America, that might be a hard sell. But, there’s more of a chance in other economies, where the banking system or the payment systems will eventually be influenced by cryptocurrencies.

For Krugman and other academics in the US, it’s not obvious to them that average consumers gain huge benefits from bitcoin relative to your standard payments network. But if you, for example, have to send money to Africa, and you have to go through all the high-fee channels, the slow channels, and so on, then there might be some benefit. When you start looking across the world, it’s suddenly not so obvious that bitcoin is necessarily at a disadvantage compared to standard channels.

Most economics research on crypto focuses on bitcoin. But, today bitcoin is part of a larger ecosystem and it seems that this ecosystem is rarely studied in much depth.

Bitcoin has got 10 years of data behind it, which is a not an insubstantial amount of data. Ethereum has a similar length of data, which makes it more feasible to study than a coin that, for example, just launched last year. But, the fundamental underlying structures of Ethereum are very different from bitcoin. Unfortunately, many economists see them as interchangeable, and it’s just a horse race, which is silly and bad and dangerous from an economic modeling perspective.

We can think of bitcoin as being designed to facilitate payments and the movement of money in an open system. At the other extreme, we can think of a company releasing a token solely for the purpose of buying or selling its product—you need to use that token to buy or sell that product. You could also think of a crypto [coin] that functions in the equivalent space of Etsy or Amazon Marketplace, where the goal is to provide a platform for various sellers to use that token.

So, you can think of these three types: the payment, the platform, and the firm-specific tokens. These have very different uses. They’re not competing directly against each other, because they are not fulfilling the same function in the economy. They’re not substituting for each other.

Your work on bitcoin and exchange rates does something rather surprising: you use bitcoin market statistics to reveal surreptitious government use of capital controls. How can cryptocurrency market statistics be used to explore economic phenomena like this?

First, I absolutely do think that cryptos can be used to study other economic phenomena—and eventually even the academic journals will agree with me, because the paper you’re talking about has now been rejected four or five times for various reasons, including the reason of “this can’t possibly work.” It tells me that the referee didn’t get past the first page because “showing that it works” is actually the point of the paper.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a twice-weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

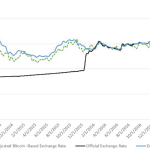

Here’s what the paper does: I take the price of bitcoin on the same exchange in different currencies. For example, we look at the average price of bitcoin sold in US dollars on an exchange and then look at the average price of bitcoin sold on that same exchange in a different currency, let’s say the Japanese Yen or the Euro. I then calculate the equivalent exchange rate you would get if you were moving a currency through bitcoin—that is, if you were trying to just convert the currency. So, if I have Euro, I buy a bitcoin with Euro, and I then sell the bitcoin for US dollars—what I’ve done is moved from Euros into US dollars at an exchange rate that’s equal to the ratio of that bitcoin price. I then take that bitcoin-based exchange rate and I compare it to the actual exchange rate. And then I look at how those exchange rates compare across time.

What I show in that paper is that, statistically speaking, for exchange rates that are open and don’t really have capital controls or market manipulations, your bitcoin-based exchange rates and your official exchange rates co-move. There might be a gap due to inefficiencies or fees, but they co-move. Whereas, for exchange rates where we know there are strong capital controls, let’s just say they don’t.

We were discussing blockchains and he was wrong and I wouldn’t let it go. So, he shushed me—it was a fascinating experience to have. I guess it’s no different from other any other economics field.

What you get is the bitcoin exchange rate spiking or collapsing and the official exchange rate just sort of saying, “100 equals one US dollar,” “100 equals one US dollar,” day after day after day. And meanwhile, your bitcoin rates exchange rate is dancing around all over the place.

It’s important to realize that countries can impact financial flows in essentially two different ways. One is to manipulate the price of their currency relative to another currency. Doing that directly is exchange rate manipulation. You can impact the international financial flows in a different way too, through a method called capital controls (like, “you cannot move your money out of my country.”) You could also have a more moderate one that says, “you can only move this much money each day, or this much money each year,” or you could have taxes that need to be paid, or fees, or fines that need to be paid. You can make the process have a lot of regulations. You could also just allow the movement to be free, but have it be very hard to flip the currency that you’ve moved in into the domestic currency.

So, there are many ways in which the capital controls can take place, which is why they’re actually really hard to capture. As well, we also know that countries lie about whether or not they have capital controls. There’s a pretty famous paper called “Fear of Floating,” where some economists showed that economies will lie about whether or not they are floating their exchange rates, and we see similar things with capital controls.

In the paper, you include this amazing chart that uses the example of Argentina, and you chart the dólar blue with respect to bitcoin exchange rates. Can you use this example to explain how you showed exchange rate manipulation?

What this chart shows is that during the time period when there was a lot of manipulation—essentially there was a peg so that the exchange rate wasn’t allowed to move officially relative to the US dollar— the official exchange rate is pretty much a flat line.

Now, what’s special is that you can actually get access to the approximate street value exchange rate. And that’s where the dólar blue—which is published in newspapers and also in official statistics—compares to the official value on a daily basis. So, I use those two, the dólar blue, which is well known, and the official statistic, which is also well known, and then compare those two exchange rates to the bitcoin exchange rate. What I find is the bitcoin exchange rate is following the dólar blue exchange rate—the unofficial street currency value of the exchange rate.

And why that’s important is that if you step back for a moment and think about bitcoin and bitcoin prices, it’s not obvious why the bitcoin prices should inform exchange rates at all. There are many reasons why it would not necessarily look like the underlying street value exchange rate. The nice thing about the Argentina example is that we do have a daily street value exchange rate, and I can show that despite all these issues within bitcoin prices, that drops out.

In the chart showing the dólar blue, there’s this very flat line that all of a sudden jumps and starts to correspond with the bitcoin exchange rate. What’s going on there?

Ah, exactly what you think! What they did with the official exchange rate is they stopped pegging it. They allowed it to free float, or float more freely. And so, it jumps up and it starts to mirror the street value exchange rate, which then also reflects the bitcoin exchange rate.

There was also a similar result for the Chinese Yuan. In 2015 they had to do a revaluation. You can really see that before 2015 it was all fine and all the exchange rates were moving together and then starting in 2015, they start drifting apart and then they re-value and then everything starts to move together again. What’s really special is that it’s actually really hard in most countries that don’t have the equivalent of dólar blue to get daily unofficial exchange rates values; the best we can normally do is monthly, and that monthly rate is self-reported.

It tells me that the referee didn’t get past the first page because “showing that it works” is actually the point of the paper.

As bitcoin scales, is this going to be a problem for central bankers? What kinds of measures might they use to take back control?

What makes bitcoin different from pre-existing money formats is its digital nature combined with decentralization, right? If you have physical currency, you can take it out of the United States, and probably at levels higher than you would expect. You could funnel it to various groups even if those groups were not legally allowed to be funded.

The difficulty is that you would have to take a suitcase full of money and make sure it finds its way there. You have this physical format of money that you have to move across borders, but then it can be seized if you have standard controls in place.

You could also send it digitally. You could send it with PayPal. But the problem is that PayPal is a central agent. So, PayPal is keeping records and you’ve got to identify yourself to Paypal and so on, and that might reveal your transactions if you tried to move money across borders. On the other hand, you no longer have to deal with physically carrying a suitcase full of money across the border.

Now, with bitcoin the difference is that it’s decentralized and in an ideal situation you could send money from wallet A to wallet B without a centralized agent keeping track. That makes it much, much harder for any regulatory authority to exert control.

And that’s what’s new. It’s much harder to control, to shut down, or detect. So, if I’m a refugee, for example, trying to bring money out of the country, previously it might have meant buying a bunch of gold or flipping a bunch of currency and trying to make it across the border, one way or the other. The digital alternative is that I could load it all into bitcoin and just walk across the border.

As a female economist studying cryptocurrencies, you’re working in two fields that have been traditionally occupied by men. Has this been a challenge?

My dad was a database architect. When he had to take me for babysitting on the weekends I’d be playing around in the server room. So, the computer science field is not strange to me. When I was an undergraduate, I was a physics major and then came into economics for graduate school. I’ve been around sort of these kinds of groups my entire life—it’s not foreign to me in that sense. I was at a recent economics conference and I was shushed by someone who did not know what he was talking about. We were discussing blockchains and he was wrong and I wouldn’t let it go. So, he shushed me—it was a fascinating experience to have. I guess it’s no different from other any other economics field.