The Wyoming blockchain movement, one of the winningest advocacy efforts of its kind in the United States, started with an act of charity. In the summer of 2017, Caitlin Long, a lanky, self-effacing former managing director at Morgan Stanley, wanted to endow a scholarship for female engineers at her alma mater, the University of Wyoming. She had donated before, but this time was different: She wanted to make her contribution not in cash but bitcoin.

She couldn’t. The law governing money transmission in Wyoming, it turned out, made bitcoin illegal. Coinbase and Circle, two of the most well-capitalized American crypto companies, were forced to abandon the state in 2015, leaving some customers locked out of their bitcoin accounts. The upshot was that UW could not legally accept Long’s donation. “When I looked into it, I was appalled,” she says.

Long has a deep connection to Wyoming. She grew up in Laramie, then a town of about 23,000, where the state’s only university is located. In those pre-internet days, it was an isolating experience. “We used to measure the size of the towns by how many McDonald’s they had,” she says. “Even today, Laramie is a two-McDonald’s town.” When she went to Harvard Law School in 1990, she found it intimidating at first; all of her fellow students seemed to have traveled widely and were fluent in multiple languages.

Yet unlike her older sister, who left Wyoming and never looked back, Long remained fond of her home state, even as a career on Wall Street took her from Salomon Brothers to Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley, where she was working in 2012 when she first heard about bitcoin. These days, having spent two or three months out of the past year in Wyoming, she catches herself saying “we”—counting herself among the state’s residents. “This is home. Whenever I speak here, I always start with, ‘Wyoming is home and always has been and always will be,'” she says.

Arrayed against them are hidebound legislators, the forces of inertia, and pretty much every banker in the region.

Long feels the same affection for UW. Her father taught electrical engineering at the university for 40 years, eventually serving as department chairman, and by the summer of 2017 Long herself had served two terms on the university’s board of trustees. “I got a much better education at the University of Wyoming than I got at Harvard—and it was much better value for the dollar,” she says. “Harvard definitely was the credential and the calling card, but Wyoming really educated me.” So when, partly for tax reasons, Long found herself looking to donate a large five-figure sum of bitcoin, UW was the natural choice of recipient. “I said, ‘It’s time. Let me share the wealth.'”

She made an end run around Wyoming law, using a Fidelity donor-advised fund to give away her bitcoin, which the university received as dollars. But it was hardly an ideal solution. She began looking for a way to change the law. Then, things just sort of snowballed. Within months, she was leading a quixotic crusade to turn her home state into the blockchain state.

—

Early Victories

Unlike in Washington, D.C., where well-funded advocacy groups have sprung up to serve Big Bitcoin, most of the Wyoming players—as I saw during a visit last November—are not paid lobbyists. What they are is a ragtag band of ranchers, cowboy lawmakers, bitcoin miners, and entrepreneurs. Chief among them are Rob Jennings, an old college drinking buddy of Long’s who spent nearly three decades as a political fundraiser in Washington; a savvy, well-connected accountant named David Pope; and Tyler Lindholm, a strikingly tall, snake-hipped young libertarian state legislator known for co-sponsoring a 2015 bill that gave Wyoming the best local food laws in the country. Their volunteer status gives their mission “purity,” Long says. Arrayed against them are hidebound legislators, the forces of inertia, and pretty much every banker in the region.

Despite this resistance, to say nothing of Wyoming’s disadvantages—it has no track record as a technology leader—Long and her band, the Wyoming Blockchain Coalition, have successfully turned their state into the most crypto-friendly jurisdiction in the U.S., and maybe in the entire world.

Caitlin Long

In 2018, Wyoming passed five landmark bills, earning the least populous state in the nation worldwide attention. The first bill exempted cryptocurrencies from state money transmission laws, while another exempted so-called “utility tokens”—digital assets that are neither electronic cash, like bitcoin, nor investments—from both money transmission and securities laws. The third enabled Wyoming businesses to employ a new corporate structure, known as a series LLC, that is well-suited for crypto projects. The fourth bill, borrowed from Delaware, made it legal to issue shares of company stock on a blockchain, while the fifth ensured that cryptocurrencies would remain untouched by state property taxes.

Years before, the charismatic Long, who has short hair, strong features, and an effervescent energy, had interned in the Wyoming Legislature as a college student; the sometimes-arduous process of turning bills into law didn’t intimidate her. Jennings remembers Long from their college days as “one of the smart kids—you know, an overachiever. She was always just very motivated and driven. She was the kid that studied all the time.”

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

Long’s impressive drive is matched by a talent for team-building. To draft the utility-token bill, she enlisted one of the few experts she knew, Peter Van Valkenburgh of Coin Center, along with lawyers from ConsenSys, a blockchain “venture studio” run by Ethereum cofounder Joseph Lubin (Lubin is co-owner of BREAKERMAG’s parent company). ConsenSys was then flush with cash and still months away from laying off 13 percent of its staff. Working pro bono, half a dozen ConsenSys lawyers helped get the bill in shape, crafting amendments and keeping in touch with Long every day through a private Telegram channel. Long’s favorite word to describe their process is “gang-tackled,” as in: “We are all just gang-tackling this.”

There were obstacles. The utility-token bill drew fire from the securities industry, and almost died on the Senate floor. Long tells the story this way: “There are 13 opportunities for a bill to die in the Wyoming legislative process, and we were right before No. 13, which was the last vote. [We] had a whip count and it was going to pass. And then the Majority Floor Leader of the Senate, Drew Perkins, walked out and said, ‘I’ve got news for you. The governor asked us to delay the bill.'” The announcement rankled. “There were some people who said, ‘Wait a minute. The legislative and the executive are supposed to be very different.’ But Drew said, ‘Look, he just asked for more time. He’s not trying to kill it. He just asked for more time.’ And what we discovered was that somebody had gotten to him. We never knew for sure [who it was], and I’ve never asked him, because this is water under the bridge. But literally we were almost at the altar; we were within minutes of the bill passing.”

Suddenly it was back to the drawing board. And there was no time. In 2018, a budget year, the Wyoming Legislature would meet for a mere 20 days, during which a full two-thirds vote of either the House or the Senate was required before any non-budget bill could be heard. The blockchain legislation had to be all but unassailable. Again the ConsenSys lawyers came through. “They dropped everything and helped us redraft that bill on a Sunday,” Long says. During a marathon five-hour conference call, they made the legislation bulletproof.

The Wyoming Blockchain Coalition have successfully turned their state into the most crypto-friendly jurisdiction in the U.S.

Somehow, miraculously, all five bills passed. “That never happens in Wyoming,” says Pope, whom the governor later appointed, with Long, to the newly formed Blockchain Task Force, thus formalizing their advocacy role. “You never come up with an idea like that and have it go through the Legislature and become law in that short a period of time. There was very little opposition. And to this day, I don’t have much of an explanation for it.”

The result was cathartic. During the floor vote on the first blockchain bill, “Rob Jennings and I both teared up,” says Long. But she wasn’t about to let the momentum dissipate. The coalition began drafting new legislation almost immediately. Now, in early 2019, with the Legislature back in session, and eight of their bills on the agenda, Long and her allies are hoping to cement Wyoming’s position as a preeminent blockchain state.

—

Cowboy State 2.0

From the vantage point of San Francisco or New York, the idea that Wyoming, the self-proclaimed Cowboy State, will become a leading destination for blockchain startups, or will be the first to integrate this cutting-edge technology into its government agencies, sounds absurd. Coastal elites, schooled in the abstractions of high finance and cloud computing, would seem to be the proper stewards of the blockchain. They breathe rare air. Wyoming’s economy, oil-stained and coal-blackened, couldn’t be more earthbound.

And then there is the culture. What some see as ruggedly authentic, others view as backward. “There are two things everybody in Wyoming has to own,” David Pope tells me, “an SUV and a gun.” The Cowboy State has the highest number of registered guns per capita in the entire U.S., 132,806 guns in a state with only 579,315 residents, according to 2017 data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. That is 40,000 more firearms than its neighbor, Colorado, which has 10 times the population. In the years before Columbine, it was common to see pickup trucks parked in Wyoming high school parking lots with rifles mounted in their racks. Students in eighth grade were taught how to shoot—and graded on their performance. Even liberal Democrats are not immune. The campaign website of Sara Burlingame, a friend of Caitlin Long’s who was elected to the Wyoming House of Representatives in 2018, showed her firing a handgun. “You can’t be anti-gun in Wyoming,” says Long. “You just can’t.”

Blockchain isn't the first issue on which Wyoming has set the pace for the nation.

And yet Wyoming has never seen itself as standing athwart history, yelling “Stop.” Most of the land making up present-day Wyoming was detached from the immense Dakota Territory, to which it had belonged since 1864. From the start, Cheyenne had agitated for separation from Dakota. In 1867, the Cheyenne Leader wrote, “Dakota is a slow coach; we travel by steam.”

Blockchain isn’t the first issue on which Wyoming has set the pace for the nation. In December 1869, while still a territory, Wyoming gave women the right to vote and hold office. (Earlier that year, a bill to grant women suffrage had failed in the Dakota Territorial Legislature by just one vote.) Suffragette Susan B. Anthony visited Laramie in 1871 and called Wyoming “the first place on God’s green earth which could consistently claim to be the land of the Free.” By the time Wyoming achieved statehood, in 1890, the Eastern states were dragging their feet, so Wyoming became the first U.S. state where women had the franchise. Wyoming became known as the Equality State.

And yet there is plenty here to confirm one’s Yankee prejudice, if one is looking for it. Entering Laramie, you pass an automobile junkyard, gas stations, a car wash, and the Chuck Wagon Restaurant, established 1968. On the University of Wyoming campus, Michael Pishko, dean of the College of Engineering and Applied Science, leads me across a grassy sward, now blanketed in snow and crisscrossed by deep footprints. Known as Prexy’s Pasture, the large open area, hemmed in by classroom and administrative buildings at the academic heart of the campus, is reserved by longstanding rule for the university’s president to use for grazing horses. (The rule is no longer enforced, but even so.)

Cardano cofounder Charles Hoskinson recently moved his startup, IOHK, to Wyoming.

Caitlin Long admits that Wyoming hasn’t marketed itself well. But it’s making more effort these days. In September 2018, UW held a blockchain hackathon—the state’s first major hackathon of any kind—that drew 400 people, most of them from outside Wyoming. Participants tackled everything from ranching to healthcare, water rights to government efficiency. Long chaired the organizing committee and also spoke at the event, and she drew a constellation of prominent figures from the overlapping orbits in which she moves, including Bloq CEO Jeff Garzik, Overstock CEO Patrick Byrne, and Joseph Lubin, who served as a judge for the contest alongside both candidates for governor. ConsenSys co-sponsored the three-day event, as did Microsoft. (Full disclosure: Another speaker was G. Thomas Esmay, head of business development for BREAKERMAG’s parent company, BREAKER, which also co-sponsored the event and created one of the challenges.)

One sponsor of the event, Robert MacInnis, whose company, ActiveAether, lets users earn crypto in exchange for renting out spare processing power on their personal devices, recently moved from New York City to Jackson. A Wyoming resort town of about 10,000, Jackson is now as famous for its one-percenters as it is for world-class skiing. The most economically unequal city in the U.S., according to the Economic Policy Institute, it’s the sort of place where millionaires risk being priced out by billionaires. With more than its fair share of Silicon Valley expats, it is also—along with Cheyenne, the state’s largest city, and Laramie—one of three places in Wyoming most likely to become hotbeds of startup activity. The people there are “hungry, excited and supportive” of his plans, MacInnis says. “Most conversations end with, ‘Anything I can do, just give me a ring.'”

There is no reason, Joe Lubin told a local newspaper during the hackathon, that the next Google couldn't be built in Laramie.

Within three months of the 2018 blockchain bills becoming law, Forbes found that some 200 companies with the words “blockchain,” “bitcoin,” “cryptocurrency,” or “crypto” in their names had incorporated in Wyoming. It remains to be seen how many, like ActiveAether, will make it their physical home. There is no reason, Joe Lubin told a local newspaper during the hackathon, that the next Google couldn’t be built in Laramie.

—

Delaware Presses Pause

The first state to publicly endorse blockchain tech was Delaware. In 2017, Delaware amended state law to allow corporations registered in the state to issue shares of stock on a blockchain. Caitlin Long led that effort, too. She was convinced that tracking shares on a distributed ledger could prevent crises such as the one arising from a 2017 class-action lawsuit against Dole Foods, in which it was discovered that there were 12 million more shares of the company’s stock outstanding than Dole had thought. Other plans included using the technology to automate Delaware’s filing system for secured corporate loans. Businesses would be charged a premium to rid themselves of burdensome paperwork, bringing in what Long estimated would be hundreds of millions of dollars in new revenue for the state.

Long was then president of the blockchain startup Symbiont, Delaware’s technology partner in its effort to spin up a distributed ledger for the state. She had to watch as the Delaware Blockchain Initiative, which launched in 2016 under then-Gov. Jack Markell, slowed to a crawl under the new governor, John Carney. As would happen later in Wyoming, the secretary of state’s office put up roadblocks, seemingly because a blockchain system would cut into the livelihood of registered agents. Corporate filings are their bread and butter. The software Symbiont built for Delaware never launched. “Delaware was out in front, and now they’ve slowed it down,” Andrea Tinianow, the former director of the Delaware Blockchain Initiative, said last February. “It’s like somebody pushed the pause button.”

"Delaware was out in front, and now they've slowed it down."

Gradually, Long pinned her hopes on Wyoming. The Rocky Mountain state has now passed legislation doing all that Delaware’s amendments did and more. “Wyoming stole their thunder,” Lindholm says.

Other states are racing to catch up. In January, two Colorado lawmakers, copying Wyoming, filed a bill to exempt cryptocurrencies and utility tokens from state securities laws. In Nevada, Washoe County, which includes the city of Reno, began issuing digital marriage certificates on the blockchain in 2018, and another county, Elko, is conducting a trial to do the same for digital birth certificates.

Nevada is already attracting private blockchain firms. Last year, the $300-million startup Blockchains LLC bought up 67,000 acres of mostly undeveloped desert in the state, on which it aims to build a huge tech campus, an impregnable bunker to store digital assets, and a liveable “smart city” powered by blockchain technology.

In perhaps the oddest development, Ohio recently announced that it would begin accepting bitcoin as payment for business taxes. Tyler Lindholm was thoroughly unimpressed. “That is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard in my life,” he says. “You’re just creating another opportunity to steal people’s money.”

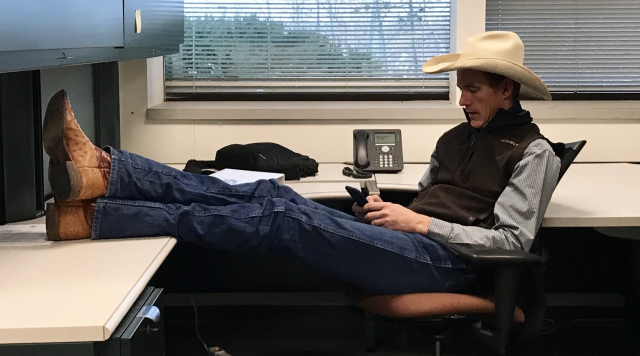

Tyler Lindholm at his desk in Leg'-Mart. Photo: Brian Patrick Eha

Wyoming, by contrast, has no personal or corporate income tax at all. But it has its own disadvantages. “Our biggest problem is, we’re Wyoming,” Lindholm says. “We’re not a well-known state. We have no municipality over 100,000 people. So that’s our downside. But, just the same, a lot of folks are still trying to catch up to us and pass our laws from last year.”

At a legislative committee hearing last November, David Pope laid it out in simple terms. “This is, really, a competition for resources, jobs, and capital,” he told lawmakers. “And the competition is not within our state; the competition is Wyoming against all of the other states and the rest of the world.”

—

Welcome to Leg’-Mart

The Wyoming Legislature, since 2016, has been meeting not in Cheyenne’s 128-year-old State Capitol, which is three years into a $300-million restoration, but in a dispiriting business center on East Pershing Boulevard. Marooned in a too-large parking lot presumably left over from the ’70s and ’80s, when it housed a Kmart and, later, a hardware store, the Jonah Business Center is a low, one-story glass bunker, utilitarian minimalist. Reflected in the mirrored facade, Old Glory flaps on a pole out front. On the parking lot sign, the Legislature gets fourth billing—below Allstate, health insurance provider Cigna, and the Social Security Administration. The building looks like the sort of place your doctor would send you to get bloodwork done. Charles Pelkey, a Democrat who represents the western part of Laramie, calls it “Leg’-Mart.”

By the time the Legislature went back into session, on Jan. 8, the blockchain bills had new momentum. In his inauguration speech the day before, the new governor, Mark Gordon, had name-checked a homegrown startup, Beefchain, and urged the state to “do more” to attract and foster innovative businesses. Drew Perkins, president of the Wyoming Senate, spoke of “overwhelming” support for the bills.

"Our biggest problem is, we're Wyoming."

Two of the most important bills have been the most controversial. The first would pave the way for a special-purpose bank serving crypto companies. Proponents say it’s badly needed; most financial institutions remain wary of bitcoin, and, among crypto advocates, stories of bank accounts being summarily shut down are legion. Wyoming bankers are fiercely opposed. They may not want to serve crypto startups, but they don’t want a new rival popping up to serve them either.

The other bill faced even stiffer headwinds. In its original form, it would have forced the Wyoming secretary of state’s office to replace what critics say is its outdated system for commercial business filings with one running on blockchain. The idea was that Wyoming corporations could automate their filings, while the state would reap the benefits by charging higher fees. Proponents say the new system could create new markets: Diamond distributors and art dealers, for instance, might be willing to pay for an immutable time-stamp provided by a government agency.

Wyoming is already one of three go-to states for registering U.S. business entities—the top two are Delaware and Nevada—and earns some of its revenue from corporate registrations and other filings. The secretary of state processes these reams of paperwork, in some cases manually. The desire to revamp the system by which it processes them became urgent thanks to the economic downturn that hit Wyoming.

It began in mid-2015, after the price of crude oil plummeted by nearly 50 percent in less than 12 months. The following year, with the shale boom providing cheap natural gas and the Obama administration laying new regulations on coal, the three largest coal firms in Campbell County declared bankruptcy. Hundreds of miners in Campbell County, the center of coal production in Wyoming’s mineral-rich Powder River Basin, lost their jobs. So did thousands of other workers throughout the state. Joblessness became common, even as the unemployment rate was falling in neighboring states. Soon Wyoming was hemorrhaging residents. Between mid-2015 and mid-2017, the state’s population dropped by more than 12,000, its worst decline since 1989.

Wyoming has long ridden a boom-and-bust cycle, its economy—and state government—heavily dependent on natural resources. This was the bust. In the 2016 elections, economic diversification became a watchword. As Tyler Lindholm says, not every kid wants to be a cowboy or a coal miner or work in the oil fields when he grows up. And while the oil and gas industry are recovering, lawmakers are still grappling with a deficit that has caused deep cuts to the Department of Workforce Services and other state agencies.

Blockchain could be a way out of the hole. By touting its tax advantages—and new, exclusive blockchain-powered services—Wyoming could make a mint off the businesses it would attract. “This has the potential to significantly change what the secretary of state’s office brings in on the filings,” Ogden Driskill, a state senator and fifth-generation Wyoming rancher, told a legislative committee last November. Delaware earns 37 percent of its total revenue from business registrants, some $1.5 billion annually. If Wyoming could claim even five percent as much, it would mean adding $56.5 million a year to the state coffers. Ten percent would be real money.

This has the potential to significantly change what the secretary of state's office brings in on the filings.

There was just one problem: The secretary of state, Ed Buchanan, was dead set against the bill. At the hearing he was visibly chafing at the idea that the Legislature might force him to build a system he didn’t want to build. He could admit the “excitement” of blockchain technology, he said, but it was hard “to be an advocate” for it when he hadn’t received a satisfactory answer from the Task Force as to why it was so essential. “How does what it will actually do justify the cost? I don’t have an answer for that,” he said. He respectfully suggested to the committee that “your time and your talents are best utilized elsewhere”—anywhere, that is, other than strong-arming his office.

By early February 2019, the bill had passed the Wyoming House and was on its way to the Senate, but not before being neutered. The all-important “shall” had been replaced with “may”—making the new filing system optional, not mandatory.

Long and her allies knew the 2019 bills would be contentious. The first batch of legislation might have changed some things. But now the Wyoming Blockchain Coalition is looking to appropriate funds and drag government agencies and industry groups out of their comfort zones. “It’s not going to be as easy this time,” Pope told me late last year. “I believe that it will happen, but it will be a fight. It will require all of our collective skills, contacts, and everything.”

—

Panning for Gold

What could possibly draw blockchain startups to Wyoming, apart from legislation that other states could one day copy? State boosters point with pride to two factors. First is the near total lack of taxes. The Tax Foundation has rated Wyoming’s tax system the most business-friendly of any state for the past 10 years in a row. Delaware and Nevada are No. 11 and No. 9, respectively.

The second factor is the invention, in 1977, of the limited liability company. Dreamed up by lawyers and accountants working for the Hamilton Brothers Oil Company, an LLC combines the virtues of the partnership and the corporation, shielding the personal assets of its owners from business liability. At first, the Internal Revenue Service frowned on the concept, but today two-thirds of new business formations are LLCs. Perhaps because of its prescience, Wyoming continues to attract more new LLCs than almost any other state. There is nearly one LLC for every two people in Wyoming today.

Caitlin Long sees an ideal match between the private LLC structure and digital token offerings, which allow businesses to raise huge amounts of capital without having to go public. For crypto projects, a series LLC could be even better. The open-source code would be held by the parent company, while each project built using that open-source software would be structured as a separate LLC, isolated from the others in case of bankruptcy. The number of children, or subsidiaries, is theoretically infinite.

"There's a big contingent in the state that loves the fact that we're only 580,000 people."

With all this synergy, why is Wyoming not a magnet for startups? The landscape is its own answer. It’s huge and often desolate, and towns are connected in this vastness by long highways vulnerable to wind gusts that can reach upwards of 70 miles an hour. Wyoming is the ninth-largest state by land area, nearly 100,000 square miles, but its residents consider it a small town with very long streets.

“It’s cold, and it doesn’t have transportation infrastructure that makes it as easy to get here,” says Long. “And it’s rural. It doesn’t have the city life that naturally attracts a critical mass of people. But we’re going to change that.”

Businesses are starting to respond. IOHK, the company behind billion-dollar cryptocurrency Cardano, announced in January that it was relocating from Hong Kong to Cheyenne, drawn by the pro-crypto atmosphere. On Twitter, Cardano CEO and Ethereum cofounder Charles Hoskinson called Wyoming the “CryptoFrontier.”

Not everyone is happy about an influx of new people. “There’s a big contingent in the state that loves the fact that we’re only 580,000 people,” Michael Pishko tells me one afternoon several months ago, in his office at the UW engineering building. Between us is a glass table scattered with papers. The dean, a cheerful, robust-looking man with a freckled scalp and a reddish windburned face, earned his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin in 1992, before the tech boom turned Austin into a metropolis of nearly one million people. He has no desire to see Cheyenne or Laramie similarly transformed, but he does want UW to produce nationally competitive graduates. Today, that includes graduates with blockchain expertise.

In the spring of 2018, UW joined New York University, Princeton, Berkeley, and MIT as one of a handful of American universities offering classes in cryptocurrencies or blockchain. In UW’s first course, students sought to develop a blockchain voting mechanism. This semester, the university is offering an Ethereum development class taught by Beefchain’s chief technology officer. Pishko’s ultimate goal is for UW to be the first to offer a full minor degree in blockchain. For that, he’s trying to get $5 million in matching funds from the state so he can hire four new instructors, all blockchain specialists: two in computer science, one in agriculture tech, and one in fintech.

I ask Rep. Jim Blackburn, who supports the blockchain bills, what he thinks of the university’s aim to create local talent for cutting-edge startups. “We don’t even really know what could come out of this,” he says. “It’s kind of like gold mining, right? I don’t know if there’s gold in that creek or not, but if I don’t stick a gold pan in there and find out, I’ll never know.”

—

Coal, Cattle, and Crypto

There is another cohort not eager to see Wyoming become the blockchain state: bankers.

David Pope ran headfirst into their opposition last fall, when he gave a talk on blockchain to the Southeast Wyoming Estate Planning Council. Among the finance professionals, CPAs, and attorneys in the audience was a staunch opponent of the blockchain movement, Jeff Wallace. The source of his antipathy wasn’t hard to guess. The bald, ruddy-faced CEO of the 100-year-old Wyoming Bank & Trust is not inclined to look favorably on a new competitor, which is exactly what the Blockchain Task Force’s special-purpose bank bill aims to foster. He and Pope shared a mutual respect, but for the moment they were natural enemies. They met in the middle of the room to shake hands before retreating to opposite corners, like prizefighters in business attire.

David Pope

In simple terms, the bill paves the way for someone to open a new type of state-chartered bank in Wyoming, one with a narrow but crucial function: to provide risky businesses with a conduit to the traditional financial system that won’t ever be shut off. After years of bad experiences, crypto startups “are constantly living in fear of losing their bank accounts,” says Long. Because the special-purpose bank won’t be FDIC-insured, it will be required to keep 100 percent of deposits on hand, so it can’t make any loans. It will be “essentially just a money warehouse,” Pope told his audience. As long as a company can pass standard compliance screenings, the special-purpose bank won’t be allowed to discriminate against it.

For blockchain companies, such a bank would be a powerful draw. The Wyoming Bankers Association sees the bill as an affront.

“This bank really doesn’t do anything different than what a chartered bank is currently able to do,” Wallace, a tall man with an ample stomach protruding over his belt, said when Pope had finished. His larger concern was a provision in the bill that if the special-purpose bank were “denied authorization to access any [essential] services”—such as the ability to accept deposits from other banks—the attorney general of Wyoming would be obliged to sue on its behalf. He didn’t want Wyoming to have to sue the Federal Reserve. He wrapped it up: “If a blockchain company wants to come in and start up their own bank, they can use the current banking regs that are on the books right now.”

"There are a lot of politically incorrect industries that are based here. Tyler always likes to say, 'We do coal, cattle, and crypto.' Now throw in firearms."

Pope, leaning on his podium, was unperturbed. “This is an area where we have to have dialogue and discussion,” he said in a conciliatory tone. “But it is an issue. … And we have to figure out a way for a legal business to operate and have a bank account.” He was thinking of payday lenders, firearms dealers, coal producers, and other “high risk” businesses that had been denied access to financial services in the past. Under President Obama, the FDIC and other federal agencies had throttled the banking relationships of these businesses in an action known as Operation Choke Point.

Wallace and his brethren fought it all the way, but on Jan. 29, the bank bill passed the House. At the 11th hour, Tyler Lindholm, who even in a gray suit and tie radiates a rugged Marlboro Man vitality, had to stave off a “poison pill” amendment with which the bankers tried to sink the legislation.

It’s hard to make sense of their objections. If they want to bank the crypto community, they have nothing to fear from a rival that can offer only limited services. If they don’t, they have no reason to care, since they won’t be losing any potential customers. What’s more, no special-purpose bank will be opening its doors in Wyoming until late 2019 at the earliest. And besides, says Caitlin Long, there is something about the bill that fits with the frontier ethos—something just so deliciously Wyoming. “There are a lot of politically incorrect industries that are based here,” she tells me. “Tyler always likes to say, ‘We do coal, cattle, and crypto.’ Now throw in firearms.”

—

Cattle Futures

Powerhouse states, such as New York and California, tend to make few legislative concessions to attract businesses, unless those businesses are Amazon. They expect jobs and capital to descend on them as naturally as rain falls on the earth. Small states have it harder. If they want to punch above their weight, they have to be willing to take drastic measures.

There is precedent for a small state bootstrapping itself out of a recession by changing its laws. In the early 1980s, hoping to attract lenders, South Dakota lifted its cap on interest rates and fees. Citibank promptly moved its credit card business to Sioux Falls, then a city of barely 80,000 people, and other major banks, including Capital One and Wells Fargo, followed suit. Today, South Dakota boasts tens of thousands of finance jobs and holds $3.1 trillion in bank assets, more than any other state in the country.

Clearly, Wyoming’s blockchain bills are meant to bring it the same sort of prosperity. Caitlin Long is encouraged by signs that people are starting to come back to Wyoming, that the exodus is easing if not yet ceasing. “It’s not a huge number of people, but it’s already starting,” she says. In 2018, after the money transmission law was changed, Coinbase reentered the state.

In December, Beefchain tracked 10 cows from Wyoming's Murraymere Ranch all the way to the slaughterhouse and on to an upscale restaurant in Taiwan.

By early February, the coalition’s legislative victories are piling up. All eight blockchain bills have passed in either the House or the Senate, and are set to cross over to the other chamber the following week. Momentum is building for a resounding victory. Among the crypto hopeful, battered by the long bear market and jaded by regulatory crackdowns, a meme takes off online that Wyoming—this magical realm where pro-blockchain legislation exists—isn’t real, can’t be real.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

Other states, meanwhile, are rushing to copy Wyoming. Utah and Oklahoma have both introduced legislation based on Wyoming’s blockchain bills. But the Cowboy State has no intention of giving up its lead.

Through a private Telegram channel, Caitlin Long spells it out for her allies: “The reality is no other state will be able to catch up to Wyoming.” Doing so would require enacting “well over 100 pages of statutory language,” and legislatures rarely make such sweeping changes all at once. A recently introduced bill in South Carolina, she goes on, “doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface.”

Long is betting her own money that Wyoming will win out. She and her boyfriend, Steve Lupien, who runs a blockchain trade association, are equity partners with Rob Jennings and Tyler Lindholm in a local venture called Beefchain, which uses a blockchain to track and prove the provenance of quality beef, as Walmart aims to do for leafy greens. Last spring, as a test run, Beefchain geotagged 1,600 head of cattle across seven Wyoming ranches. Jennings says he hopes to have 20,000 to 50,000 cattle—the livestock of 50 to 100 ranches—tagged by the spring of 2019. In December, Beefchain tracked 10 cows from Wyoming’s Murraymere Ranch all the way to the slaughterhouse and on to an upscale restaurant in Taiwan. Diners could scan a QR code at the table and be taken to a website that explained the history of the beef and details about the ranch.

Photo by Holly Mandarich on Unsplash

In a food economy where well-raised beef often gets mixed in with meat from other cows, and where packaging labels make unprovable claims, the certainty that blockchain provides could be a game-changer. Dozens of ranches in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and Alabama have expressed interest, Jennings says. Tyler Lindholm’s family ranch, however, is not one of them. “It actually terrifies my dad,” Lindholm says. “He’s a lot more cautious than a lot of folks.” But his sister and brother-in-law are more forward-thinking. Their ranch is taking part.

—

A Strike Against Delaware

The last major piece of the puzzle, in Long’s view, is another new bill, introduced after the 2019 legislative session was underway. If it passes, it will set up a dedicated business court in Wyoming, offering corporate litigants for the first time a swift, low-cost path to justice.

The bill is a direct strike against Delaware. Delaware is famous for its Court of Chancery, where two-thirds of the Fortune 500 and more than half of all publicly traded American companies bring their grievances and hash out their disputes, not before a jury but before a judge who is an expert in corporate law. (The court, borrowed from English common law, dates back to 1792.) When new businesses are deciding where to incorporate, Delaware’s special court and immense body of case law are powerful enticements.

The “Delaware Advantage” is precisely what Long and the others want to erase. For that matter, they want to erase Nevada’s as well. Since 2006, Wyoming’s other chief rival has had a business court system of its own, with judges in Las Vegas and Reno handling all kinds of complex disputes. “Many attorneys have privately told me this is the main reason why they continue to recommend that their startup clients register in Delaware or Nevada instead of Wyoming,” Long told the Legislature’s Corporations Committee in a letter.

Wyoming has a chance to set legal precedent for years—perhaps decades—to come.

Sooner or later, such a court would surely be called upon to rule on matters pertaining to cryptocurrency and blockchain. Be it a lawsuit against a token issuer, the legal implications of fixing bugs in cryptocoin protocols, or some other issue, Wyoming has a chance to set legal precedent for years—perhaps decades—to come. Let Delaware have its 200 years of case law, let Nevada have its utopian city in the desert. If the package of bills now before its legislature passes, Wyoming will cement its status as the most pro-blockchain state in the country, and will be that much closer to weaning itself off fossil fuels. If you believe that blockchain will unleash a tide of new wealth and jobs, like the personal computer and the internet before it, then it becomes possible to contemplate a future in which Wyoming seriously challenges Delaware as the preeminent business jurisdiction, the prime nexus—legally, if not physically—of corporate power in America.

Or, as David Pope put it in late January, “The days of smug condescension toward Wyoming are over.”

That is the future Caitlin Long envisions. Not that she expects it to manifest any time soon. The final votes have yet to be cast, and anyway, she always knew the blockchain bills wouldn’t be like marijuana legalization, where a switch got flipped and overnight you had a booming new industry. Her efforts will take years to bear fruit. Meanwhile, the Blockchain Task Force has only one year left to create change; unless its mandate is renewed, the group will be dissolved in early 2020.

But its impact will be lasting. A telling moment came in a legislative hearing last fall, when Rep. Jared Olsen, a tall, pink-faced 31-year-old attorney, married with three kids, got up to testify. Naysayers on the Corporations Committee were pooh-poohing the claim that Wyoming risked falling further behind Delaware and Nevada unless it enacted the blockchain bills. They doubted that Delaware and Nevada were really intent on taking the lead.

“Wyoming has an opportunity to take that bull by the horns,” Olsen replied. “We’re not talking about how little Delaware has done or how little Nevada has done. We’re talking about how much Wyoming can do.”