The cryptocurrency community is packed to the gills with figures fascinating for their burned bridges, depravity, stubbornness, scar tissue, and sheer, unmitigated volume. In that sea of wailing, Trent Larson manages to stand out by being the opposite: quiet and subdued, except for the nitroglycerin he stores in his brain.

Though he’s not a fan of titles, Larson is Principal Software Developer for Medici Land Governance, one of a dozen-odd projects under the auspices of Overstock.com’s Medici Ventures. He is gangly, quick to smile, and speaks with a gentleness in keeping with his Mormon background. His hair is a crisp flat-top, and on the day we spoke, he wore a pressed, button-down shirt and slacks, finished off with a pair of shiny penny loafers (without any apparent irony). At first blush, he might be mistaken for a fifty-something reincarnation of Fred Rogers, a youth pastor, or the manager of a prosperous small-town plant nursery.

Those impressions could hardly be more wrong. The clean-cut Larson is a self-proclaimed, vocal anarchist, and he believes any number of incredibly dangerous things about government, community, and trust. His dangerous thoughts are what led Larson, a computer science PhD and lifelong developer, towards cryptocurrency and blockchain, and eventually to Medici. He now leads an effort to build blockchain-based land registries, often in places—like Rwanda and Zambia—where the appeal of incorruptible property records is clear. He’s also the founder of a small anarchist group north of Salt Lake City, not far from where we first met at the Off Chain crypto and preparedness conference.

He believes any number of incredibly dangerous things about government, community, and trust.

We talked about putting land on the blockchain, the difference between an anarchist and a libertarian, and the tension between community and authority. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In Medici Land Governance, how are you applying blockchain to land administration? There’s been a lot of talk about tokenizing real estate.

Right, and we see that in the future. But I’ll just walk through a couple of our projects.

In Teton County, in Wyoming, they’ve got all of their records digitized, so we’re writing all of that to a chain. So basically it’s verification of their current documentation, and in the future as they make changes, we will keep writing those changes as well. So, it’s not like a token that’s being passed from owner to owner. It’s one recorder, putting this out there.

Now, let’s contrast that to some other initiatives like the Rwanda project, which is a paperless registry. Rwanda is fascinating, because they’ve created this public key infrastructure for their whole country. Someone can go to the ministry [office] and register themselves. They fill out a form and they’re given a code to login later, they go home, and from their own computer, they generate their keys. So they really do have ownership of that private key, and nobody else does. And then they get into a website and do an interaction that basically validates their public key. Then they give that to the government to correlate their information.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a twice-weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

That’s basically all of the systems needed to take your private key, sign something, and for somebody else to verify [the signature], because they have your public key. So if I want to initiate a sale of my property with somebody, I can sign the terms of my contract, and pass it along. The buyer gets it, and they can actually verify if this is the real person they’re expecting to contract with. Then they sign as well, and the registrar at that point says okay, yep, I recognize user one and user two. I will make it official.

It’s another case where the tokenization isn’t as important as this infrastructure for signing the agreements. And some parts of that will be public information. The fact that we’ve got a signature for some of the data that can be on-chain, and audited later, and it’s public, is, yeah, very useful.

Are you date-stamping documents that are stored elsewhere, or are you putting entire datasets onto a blockchain?

We are putting some data in the blockchain. Wyoming is a case where we are putting all of the metadata for those records on-chain. We are also hashing some scanned documents for reference. Those wouldn’t go on-chain, because it’s too much data. But the hash is on-chain.

And that makes it possible that in the future, somebody would be able to go into the chain and see that, say, a year ago, somebody had this document. This isn’t something that was just created a day ago, I have this history. And if any element of that document was changed, you don’t get the same hash. It is the government that’s initially doing this contract with us, and it’s great to see that they’re willing to put this on a public chain, which will preserve that history for everyone. It also provides a nice interface for anybody who wants to search the data, because it’s a common data structure.

How long has this project been going on?

At the end of 2017, Patrick and Hernando de Soto started working together and planning [a property data project to be known as De Soto Inc.]. And we actually worked together with Hernando for the first half of 2018, but there [are] certain terms that they haven’t been able to totally agree to [yet]. So about the middle of the year, we stopped working as much in Peru, where we were planning to deploy that one.

[But] Medici Land Governance is new as of [June] 2018 . . . and we’ve always been looking for other projects, so we have about four underway at this point. We got this project in Zambia [last July]. We signed the MOU for delivering 50,000 titles, to some areas that are informal and didn’t have titles. We put together an Android tablet app, and we employ about 100 enumerators to go on the ground, walk door-to-door, gather people’s information, and then bring that back to be correlated with land use planning, and where roads had to be, and also look at their IDs and see if they match.

When you meet anarchists, you'll quickly learn they really are trying to build connections with each other.

How do you make blockchain sound compelling?

Blockchain is compelling to some people because they realize this is a way to be open, to show that there’s some transparency to whatever process it is. And land is a natural fit because, unlike, say, wine or supply chain or voting, a lot of records for land are public, and we want it to be that way. Being able to somehow prove that I’m the owner of that, or I have certain rights, water rights or things like that, is useful. But if you look at a traditional system, it’s in an office at the county seat. It’s not necessarily all that accessible, even when that already exists.

So, for example, Wyoming is one where you’ve got names that are going to be published on a chain, and it will be searchable by name, as well as some other metadata that’s in there. So, you can make it easy to point on a map and find out who exactly owns that. Government officials want this to be trustworthy, something that is persistent in the future, and open.

Some of the chaos in certain places is because of corruption, so even if you have a government office, whether it’s paper files or a central database, that’s not entirely trustworthy.

Absolutely. Rwanda has tried to weed out corruption. But there are downsides to using this technology. People make mistakes, so you really have to be able to support coming back later and saying, “Hey, we got a judgment that says this is different, so we have to record that difference.” If we treat blockchain as this log of all the history of things that have happened, what you’ll find is, “hey, a year ago, we had a transaction, it’s written there, everybody can find it.” But today, we’ve got to go back and make a change to that. Somehow tie back to that previous one, so we have a reference to it. So we’ll see the whole history.

What was your personal entry point with blockchain?

Like everyone else—you hear about bitcoin and then sit on it for a while. And I think I made my first buy in 2011. I thought, Oh, bitcoin is going to be 10 bucks for, you know, my lifetime, so I didn’t buy very much.

Thankfully, through the meet-up here, I heard Patrick Byrne. Patrick got connected with the guys from Counterparty, and they were representing assets on top of the bitcoin blockchain. And Patrick actually hired two of the [Counterparty] guys, and in October of 2014 [I heard] that Overstock was hiring people for this project, and I applied and got in.

Then two weeks later the Counterparty guys, said, this has been fun, but we haven’t been able to come to terms. And Patrick said, okay, keep going. From the beginning, the target was an exchange, so from 2014 to 2016 we were working on tZero full time, or what became tZero. Then into 2017, Medici really grew into what it is today, with different categories of investments.

Are you a Mormon?

I have been all my life. I still go [to services], but I really don’t believe some of the basics anymore, such as, you know, the need for a God and things like that.

I’m very curious about the relationship between Utah, the church, and politics. You started something called the Bountiful Voluntaryist Community.

Yeah. I started a bitcoin meet-up, and that ran for a little while. But you know, we always have this desire to connect with like-minded people, so I started this one. We talk philosophy, but the goal is to do things that are practical, to actually do projects that show, we really are building our community. So we have a meet-up every Saturday, and we’ve been doing activities like shooting education and training, and neighborhood clean-ups, and things like that. We feel that one of the big weaknesses we have in society nowadays is we’re not connected to each other. We rely on these institutions, such as government, to solve problems for us. And that’s gonna bite us in the butt.

I hear you sometimes use the word “anarchist” to describe yourself.

Yes. I could use that to describe myself.

But “voluntaryist” is a bit more marketable. Is the term “anarchist” misunderstood?

It’s currently associated with brick-throwing rebels, I guess, who just will do anything to fight against the system and smash things and hurt people. That’s the connotation.

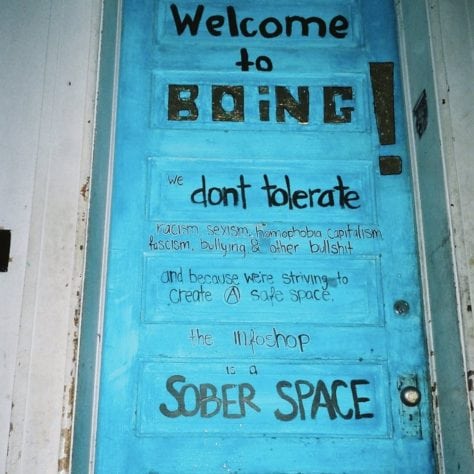

But there’s an anarchist collective downtown [in Salt Lake City] called Boing! Anarchist Collective. They had this great big “End Capitalism” sign up for a while. And at least up until last year, three times a week they would go and gather free food that was being thrown out by local grocery stores, and just offer it free to the community. And they have lots of social activities that they do just to get together.

But there’s an anarchist collective downtown [in Salt Lake City] called Boing! Anarchist Collective. They had this great big “End Capitalism” sign up for a while. And at least up until last year, three times a week they would go and gather free food that was being thrown out by local grocery stores, and just offer it free to the community. And they have lots of social activities that they do just to get together.

So when you meet anarchists, you’ll quickly learn they really are trying to build connections with each other. And yeah, for one reason or another, they’ll have a problem with current institutions, whether it’s the state or corporations. But the focus really is on peace, love and harmony.

Did your beliefs drive your interest in cryptocurrency?

Yeah, everything’s been my core beliefs, and I really am lucky to be here working in an industry that supports my beliefs. That’s something I would encourage everyone to work towards.

Get the BREAKERMAG newsletter, a twice-weekly roundup of blockchain business and culture.

You’ve used the term anarchist, and voluntaryist, but not libertarian. Do those have a distinction that you think is meaningful?

Most libertarians I know still believe in some kind of hierarchy when it comes to politics, and a state military, or the need to protect our boundaries. I think most libertarianism has that aspect of, well, we need to have a limited government, but we still need to have some of it.

There are people who would self-identify as libertarians, who are very intelligent people and who I trust a lot, but they still believe in things that I think are wrong. We in the U.S have the best genesis [as a] country you could have. We don’t have a monarchy, everybody’s living by the rule of law. But we have seen how even that fantastic start has morphed into something [else]. We have executive orders right and left. Whatever [the government] feels they can get away with, is what goes.

As a society, either we’re hungry for safety and we need to have a government to protect us, or we feel like that’s the only way to get the rule of law. Anytime we think that some authority has to control us, we’re giving up power, and it’s going to end up hurting us. We’re basically complicit in giving them the authority to take away rights from my neighbor, and I think that’s something we really have to get away from.

I know libertarians who are completely anti-government, anti-regulation, anti-military, anti-borders. But my take is often that the libertarians simply excise the community aspect from their thinking. I associate libertarianism with people like Peter Thiel, who believes the wealthy should simply go live on a private island.

I think that’s common perception, and maybe reality, that most libertarians are like ‘me first, I need to protect myself.’ I believe that there are cases like that, but part of me believes that’s just bad branding. I think most people who are libertarians tend to focus on making companies, because they know they need cooperation, and that’s the way they think of it, in a company aspect and profit aspect.

Whereas, from the right side, the [anarchist] left is perceived as wanting benefits without having to do the work for it. And both of those perceptions I think are wrong. There’s a lot more overlap in the core of each philosophy than people tend to see.

There are more negatives to [financial enforcement] than positives. If you took all of the police out of society today, it's going to be much the same as we are now

The Mormon church has very strict moral guidelines, and they have co-opted certain parts of the state to enforce them. Like Utah state-owned liquor stores. But there is an upside—Utah has some of the lowest drunk-driving rates in the country. Salt Lake is known as clean and peaceful. Aren’t there some benefits to rules, imposed either by social pressure or by the state?

Let me distinguish between cultural norms versus state control. I think there’s usefulness in social pressure—my neighborhood thinks it’s bad for me to drink, and I view that as a good social pressure, though it can go too far. But you should be working through your problems, rather than giving that up to the state and saying, ‘okay, now we’re going to legislate and send police after you if you break certain rules.’

I feel like we actually have more of our benefits [in Utah] because of cultural pressures than state pressures. I don’t subscribe to ‘hey, it’s the police to keep us safe.’ Do police really make it better? No, it’s that we have a culture here where we’ve had that respect. Maybe it’s because we’re still 150 years after some very independent and community minded pioneers got together, and generations of that strong community is still in our bones and in our upbringing.

I’m going to throw you a counterexample: the entire ICO mess. You had a sudden void of authority, and there were grifters and charlatans who ran into that gap. And now we’re getting some police action through the SEC. That’s an instance where some sort of enforcement might be beneficial, right?

Okay, disagree.

ICOs, when there are so many that are so scammy, people have learned, we’ve got to start vetting things better. The only reason they came about is people want to quick-buck, and so they’re going to be bitten. So, no, I don’t feel like just [the SEC’s] actions have made this safer. It’s because people learn that, ‘okay, here’s what I have to look for a good business model that I’m going to invest in.’

Then there’s the downside of all the SEC action, which is basically choking off really good initiatives. I was talking to someone about how FinCen is going after every transfer between tokens? That’s a crazy idea. This is one of the huge benefits of being able to have this new digital system, so taxing every single transaction is one of the worst strangleholds that we have. There are more negatives to [financial enforcement] than positives.

If you took all of the police out of society today, it’s going to be much the same as we are now. People will have to take more responsibility for their own security. And there’s certain things that people will have to be responsible for, if you don’t have state welfare and the state roads. But it’s entirely, I would say, evolving towards a better and more humane world.

Update 4/16/19 and 4/18/19: This article has been updated to clarify the relationships between Medici Ventures, Medici Land Governance, and Hernando de Soto. Medici Land Governance is a wholly separate legal entity from DeSoto, Inc.